The Gaza genocide grinds on. A year ago I wrote about it (A short, short history of a long, long confrontation) and it feels like things are even worse now.

It has been reported that more than 500 Palestinians have been shot and killed while desperately trying to get food aid to keep starving families alive. It was claimed that Israeli soldiers had been ordered to fire on them. This week, for the first time, the Israel Defence Force admitted it had fired on some of these.

This has been an outrageous war, from the raid by Hamas which killed and brutalised around 1200 Israelis, none of them “legitimate” targets, through to the Israeli response which has led to somewhere between 55 thousand and 80 thousand Palestinian deaths – many of them women and children and many of them clearly not Hamas fighters.

There has been plenty of Christian protest against the Hamas murders, but far less against the Israeli response. Why is that?

It’s complicated

On the face of it, it seems obvious that both sides have (again) gone way beyond any possible justification.

Palestinian suffering

As I outlined in A short, short history of a long, long confrontation, Palestinians have been losing land and freedoms since the establishment of the nation of Israel in 1948.

- Israel hadn’t been a Jewish nation since the first or second century, yet Palestinians were forcibly displaced to re-create a Jewish state – something almost unprecendented in modern history. The land was divided more or less 50/50 even though Jews made up only 30% of the population.

- Right from the start, Israel made plans to increase their share of the land, and after defeating Arab armies already had control of 75% of the land.

- Since then, Israel has occupied or taken control of much of the remaining Palestinian land and oppressed Gaza. The UN International Court of Justice has said this occupation is “unlawful”.

With this history, it is little wonder that Palestinians feel aggrieved and desperate. Hamas is the extreme expression of that frustration.

Israel’s expectations

Jews had been persecuted by European and other countries through their long diaspora, culminating in the horrors of the Holocaust. Re-creation of the state of Israel was a response to this. Many Jews felt they had a right to the whole land.

As soon as the British left the country after the establishment of the state of Israel, Arab armies attacked, unsuccessfully. This only gave Israel opportunity to take further land and displace another 700 thousand Palestinians.

And so it has continued. Militant Palestinians make generally futile efforts to preserve honour which give Israel plenty of reason or excuse to further tighten its grip on the land and the lives of the Palestinians.

Even handed?

It is easy to take sides and hard to be even handed. But a dispassionate look at the facts indicates terrible actions by combatants on both sides. How can Hamas’s murderous 2023 raid ever be justified? How can the deaths of tens of thousands of mostly non-combatant Palestinans in response ever be justified?

But Christians have generally been much stronger in condemning Hamas than condemning Israel. And many seem to be supporting the genocide in Gaza.

Christians and Israel

The positive Christian attitude towards Israel is based on statements in the Old Testament, where God promises to give the land of Canaan to the Israelite people (e.g. Genesis 15:18-21, Jeremiah 32:36-42). Many Christians see the promises renewed in the New Testament, though I don’t see that (see below).

So pro-Israel Christians see the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 as the first step in God’s re-establishment of God’s people in their own land, in accordance with prophecy – even though Israel is currently a secular state, they believe that one day the nation will return to God. Some see efforts to oppose Israel as anti-God or even demonic.

These beliefs seem to go well beyond the view that Israel, like other countries, has the right to defend itself. These Christians seem to support Israel’s actions that go far beyond defence, and have been called “terrorism” or genocidal.

God’s people, God’s ways?

There are deep problems (in my opinion) with much of this.

Understanding these prophecies

It isn’t clear to me that the Old Testament promises about the land are relevant to the times since Jesus.

- Understanding and applying OT prophecies is not as simple as we might think.

- The return from exile in Babylon could be seen as a fulfilment of those prohecies (Jeremiah 29:10), rather than the present day.

- In the NT, Jesus changes how we should see the kingdom of God, from a physical kingdom established in a physical land by warfare, to a spiritual and non-violent kingdom that exists anywhere people recognise God as king and act accordingly.

- Genesis 15 promises the land from the Nile to the Euphrates. Does anyone think all this land is promised to Israel today?

God’s people or a secular state?

Modern Israel is a secular state. The majority of Jews in Israel are either secular, or follow the traditions without a great deal of personal faith and commitment. So it grates when Israel’s reponse is justified in religious (Tanakh or Old Testament) terms, as Benjamin Netanyahu has done.

Is modern Israel “God’s people”? I don’t know.

God’s ways?

The Old Testament expresses the view that Israel’s loss of the land was the result of disobedience (Deuteronomy 28:58–64) – worship of other gods (Joshua 23:13), mistreatment of the poor and suffering (Amos 4:1-3), especially aliens or strangers (Jeremiah 7:5-7), and waging war or doing politics without God’s approval (Isaiah 30:1-2).

Most people’s objections to Israel’s actions in Gaza haven’t been directed against the war against Hamas, but by the fact that so many other Palestinians have been harmed as well. As someone said, if a gunman was in a school room, we wouldn’t thinkj it acceptable to kill all the children to kill the gunman. So why is it acceptable to kill so many Palestinians in order to try to eliminate Hamas?

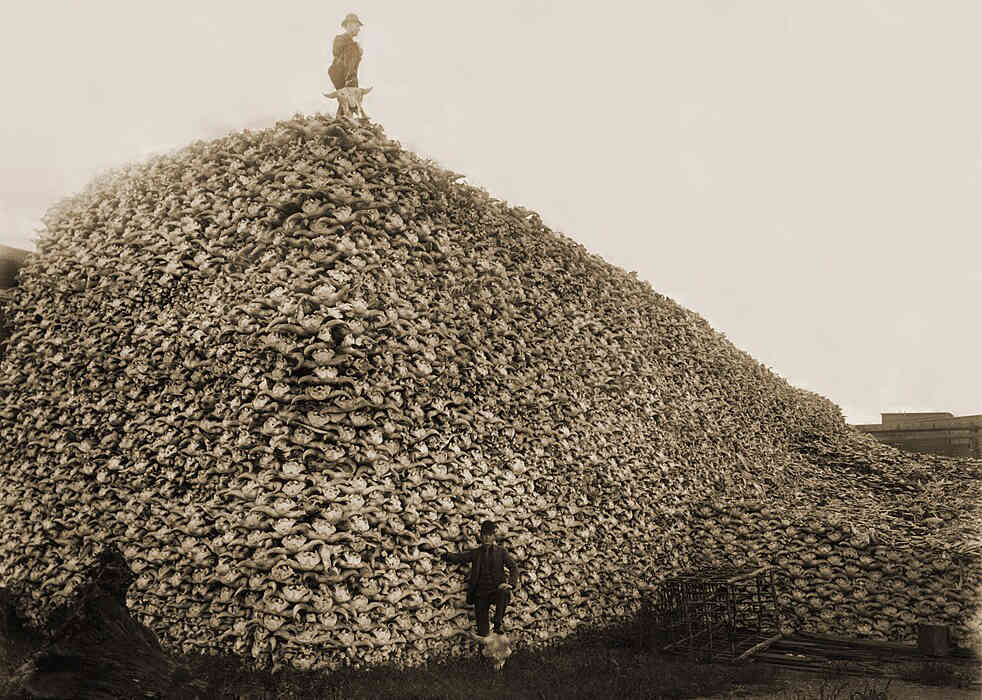

The OT limits revenge for injury to “an eye for an eye” (Leviticus 24:20), and applies the same principle for killing – effectively death for a death (Leviticus 24:17). 80,000 for 1,200 is clearly way beyond this.

It seems to me that the OT prophets would condemn Israel’s actions.

The Christian way?

Observant Jews will have their own assessments of whether Israel is honouring God (many think it is not). But my concern is with Christian responses.

Jesus called us to be peacemakers (Matthew 5:9), and to seek non-violent resolution of conflict. Of course this isn’t always possible in this violent world, but it disturbs me to see Christians explicitly relegating Jesus’ commands to personal behaviour only, despite Isaiah saying “the government will be upon his shoulders” (Isaiah 9:6).

It seems to me that Christians who uncritically support all Israel’s actions are turning their backs on Jesus’ teachings and accepting the genocidal commands of some parts of the OT as acceptable today, despite there being no command of God today for Israel to take that action.

Of course many Christians have been outspoken against the murderous actions against Palestinians. Some Protestants have spoken out strongly, and Pope Francis called Israel’s actions “terrorism”. Many Christians have advocated policies of peaceful coexistence and condemnation of excesses on either side.

Is there a balanced Christian view?

Christians must support peace-making and non-violence wherever we can.

Therefore, we must condemn Hamas’ original bloody raid that started this sorry war, even if we recognise the legitimate grievances of the Palestinian people.

Likewise we must condemn Israel’s massive and indiscriminate killing in response, even if we recognise Israel’s right to protect itself. If we believe Israel is acting as God’s chosen people, we should hold it to a higher standard, not a lower one!

But there are serious doubts about seeing this as a “holy war”. Supporting genocide believing God has commanded this in the past is bad theology and probably bad history. We are following Jesus now.

Whatever view we hold about Israel, Christians should be outraged at what is happening still.

A brief note about OT history

I have written this post as if the Old Testament contains accurate commands of God to ruthlessly conquer the land of Canaan, as this is what conservative Christians generally believe. However this isn’t the way I believe we should interpret the OT – see The Canaanite genocide – a historical perspective.

Sadly, how we interpret the Bible can have deadly and tragic implications for how we live and what we support or oppose.

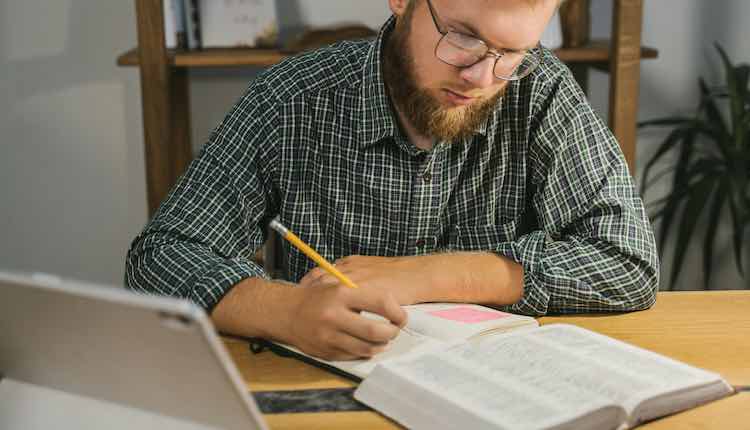

Photo: Forced Displacement of Gaza Strip Residents During the Gaza-Israel War (Wikimedia Commons).