Disarming Scripture by Derek Flood

The Old Testament world was a violent place.

For a christian, the most troubling violence is surely that said to be commanded by God, whether it be Abraham being commanded to sacrifice his son and heir Isaac, Joshua commanded to exterminate Canaanites who are unfortunate enough to be living in the “Promised Land”, the command through Elisha that Jehu should kill all the family of the line of Ahab (Joram, Jezebel and all their relatives), or many other incidents.

Christians must face the challenge: if God commanded these killings, how can we say he is loving?

This book addresses the question of violence attributed to God in the Bible, and how that can be consistent with the non-violent teachings of Jesus. And it comes with recommendations from no lesser luminaries than Walter Brueggemann, Brian McLaren, Peter Enns, Jim Wallis and Brian Zahnd.

Violence in the Old Testament

The author, Derek Flood, begins by outlining some of the commands attributed to God in the Old Testament, which, he says, include genocide, infanticide, cannibalism and rape. He points out that this appears to have left a legacy of violence by christians, used, for example, to justify mass killing of Muslims in Jerusalem by the Crusaders, an event apparently still remembered by Muslims to this day as a grave atrocity.

He examines what he sees as the two main ways christians try to deal with this problem. Conservatives commonly seek to justify God’s actions as necessary at the time to preserve the Israelites’ religious purity, as if somehow the mass killing of innocent children (among others) can be justified and believed to be loving. More progressive christians, on the other hand, tend to avoid the question altogether, and point instead to the more moral aspects of the Old Testament.

In the end, both views fail to explain how the God revealed by Jesus could command such abhorrent destruction.

The Old Testament speaks with more than one voice

Flood begins his response by pointing out that the Hebrew scriptures do not speak with one voice – there are differences of approach and progression in understanding (what famed scholar Walter Brueggemann called “testimony and counter-testimony”) – often the prophets arguing against some of the statements in the Torah. He gives examples of some of these variations, for example:

- Isaiah (1:11-15) said that God took no pleasure in their sacrifices, even though they were commended in the Law.

- Job’s friends followed teachings in Deuteronomy 28 that suffering was the result of sin, but God took Job’s side against them (Job 42:7).

- Deuteronomy 28:63 says it pleased God to ruin and destroy, whereas Ezekiel 33:11 says God takes no pleasure in death.

- The Torah (Exodus 20:5, Deuteronomy 5:9) says God will punish children for the sins of their fathers, and 2 Samuel 12:14 shows this happening in the life of David, but Ezekiel (18:17-19) says God doesn’t do this.

Thus, what are given as the clear teachings of God are sometimes later contradicted. Flood says that while unquestioning obedience to God is a major theme of the Old Testament, faithful questioning is often presented in a positive light.

Jesus and the early christians

Jesus embraced some aspects of the Old Testament in his mission, and rejected others. When he interpreted scripture, he tended to favour what was most helpful to people, especially about Sabbath laws, even if that went against the more strict interpretation of the Pharisees. He rejected the idea that suffering was a result of sin, and in Luke 4 he omitted a reference to vengeance from his reading of Isaiah when explained his mission.

Paul follows Jesus in omitting violent sections from two Old Testament quotes in Romans 15, and emphasising grace over law.

The church father, Origen, was troubled by the violence in the Old Testament and argued that the stories should be read figuratively, and many christians after him have taken this allegorical approach.

Understanding the Old Testament

The modern emphasis on understanding what the original authors meant and avoiding allegorical interpretations has emphasised the problem – how they thought back then seems very different to the ethics given to us by Jesus. How can we resolve this dilemma?

Flood points out places where God is portrayed as doing acts we would regard today as evil – creating disaster, sending evil spirits, killing children, etc, but later Biblical writers, and Jesus himself, say these acts come from the devil. For example:

- 2 Samuel 24:1 says an angry God told David to take a census, but 1 Chronicles 21:1 says it was Satan who did this.

- The Old Testament often attributes sickness and suffering to God, whereas Jesus says they come from the devil (e.g. Luke 13:16).

This suggests, he says, that the Old Testament shows the Israelites’ slow movement from polytheism and tribal war to monotheism, rather than fixed moral and theological precepts. In the beginning they attributed both good and evil acts to God, but later saw this was not so. So we see their moral development – a concept similar to the idea of progressive revelation.

Archaeology indicates that the genocide in Joshua didn’t actually happen, at least on the scale described, so these stories are at least partly legendary and serve a different purpose than actual history. “God never said to destroy Jericho,” Flood says, “not only because God is not a war criminal, but because Jericho was long empty at the time.”

Unquestioning obedience vs the way of love

Flood argues that all this shows that it is right for us to faithfully question the violence in scripture rather than be unquestioningly obedient and literal, on the basis that if we don’t act in love, we are doing wrong. We should confront the violent texts and learn from them – including about ourselves and our own propensity to violence today.

Violence and the New Testament

All this so far is reasonably straightforward. Probably most christians are troubled by the Old Testament violence attributed to God, and more and more are coming tentatively to similar views. But surely the New Testament stands without need of re-interpretation?

Flood begins his consideration of the New Testament with the attitude and teachings of Jesus against violence – forgiveness, turning the other cheek and love for enemies. With these teachings, he says, Jesus opposes the violence of the Old Testament, and replaces it with a new understanding:

- He said those who are suffering were not being punished by God, but were under Satan’s bondage.

- The warrior God of the Old Testament has become the suffering God in the New.

But the New Testament doesn’t go far enough?

Most christians would agree that the New Testament takes ethics to a whole new level compared to the old (for example, Jesus’ teachings in Matthew 5 about hate and murder), but Flood points out that there are ethical issues where the New Testament hasn’t moved so far, but only taken the “first bold and faithful steps” in the more loving direction.

The obvious example is slavery. The New Testament takes major steps away from support for slavery (which is allowed in the Old Testament) – slaves are encouraged to gain their freedom (1 Corinthians 7:21), masters are told to treat slaves fairly (Ephesians 6:9) and in Christ slaves and free are equal (Galatians 3:28). But slavery isn’t totally condemned.

We may see good reason for this – no-one wanted to stir up persecution and anyway, in the Roman Empire, many slaves were materially better off than if they were free. Nevertheless, slavery isn’t condemned in the way that we would condemn it today.

But it was on the basis of New Testament teachings that William Wilberforce and others fought to end slavery in Britain, and slavery was eventually ended in the US and elsewhere. Few christians doubt today that slavery is deeply wrong. And so Flood can conclude:

“we cannot stop at the place the New Testament got to, but must recognize where it was headed.”

Trajectory readings

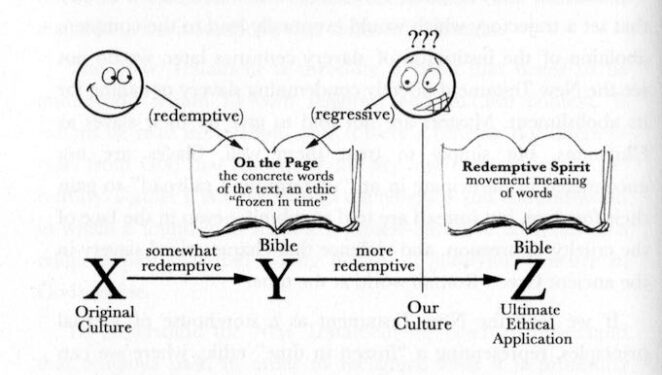

This where Flood starts to be really radical. He says we must recognise that teachings that were progressive in the first century may be seen as regressive today, especially from our vantage point of two millennia of christian ethics. This diagram shows how this works.

Diagram from page 126, showing how Flood believes New Testament teachings were redemptive at the time, but are now regressive if we take them as rules. Rather we should see them as a step along the way to where we should be.

He describes this as a “trajectory reading”, which recognises that the New Testament is not a “final unchangeable eternal ethic” but “first major concrete steps” away from the old ways of oppression.

But isn’t this risky?

Obviously such an approach leaves ethics wide open to various viewpoints, as different people see different trajectories in the Bible.

But Flood argues that we have already de facto moved in this direction with our stand against slavery and corporal punishment of children, two matters where modern culture and present-day christians have moved beyond the Biblical teachings. He argues we can no longer pretend we believe that ethics are set in stone by the New Testament. Believing in the inerrancy of scripture manifestly doesn’t lead to absolutely clear answers because inerrantists disagree strongly about many things.

So the question is, he argues, how do we know the right trajectory?

Through the lens of Jesus

Flood favours the idea that we interpret the Bible through the lens of Jesus’ life and teachings. Jesus said (Matthew 7:16) we are to judge people and actions “by their fruit”, in other words, how they work out in practice, by asking “what leads to flourishing and love?” And Paul said if we allow the Holy Spirit to transform our thinking, we can know the perfect will of God (Romans 12:2) and “judge all things” (1 Corinthians 2:15).

Jesus use of parables which contain violence presents a difficulty, but Flood argues that we have to look to see the trajectory of Jesus’ parables. He might start with the often-violent assumptions of his culture, but the parables end up subverting that culture and promoting a non-violent ethic. He says that Matthew’s gospel has the most violent version of parables, and concludes that Matthew has added this element in, but doesn’t address the possibility that Matthew’s is the more original form and the other gospel writers “sanitised” them a little.

How this works out in practice

Flood considers several examples that are controversial.

He discusses the use of violent punishment, including the death sentence and warfare, by governments seeking to right wrongs, which is considered by many to be supported by Romans 13:1-7 and several other passages. He argues that the other passages have been wrongly interpreted and that Romans 13 has to be read in the light of the much more peaceful teachings of Romans 12.

Most of these “law and order” approaches are built on the idea of retributive justice, which is based on punishing offenders. He argues that this is not Jesus’ approach, who was always looking to rehabilitate offenders (e.g. Zaccheaus or several women accused of sexual sins), which is restorative justice. He gives examples of how neuroscience and actual government justice programs in the US and elsewhere show how we can use restorative justice effectively and with better results than retributive programs.

The same restorative justice principles, he says, can be used in parental discipline

He argues that, even though there is no sign of any trajectory towards acceptance of LGBTQI relationships within the Bible, modern christians should support a more inclusive approach because it leads to greater flourishing (the LGBTQI community has higher rates of drug abuse, mental illness and suicide because of discrimination, particularly by christians).

Finally, he addresses the question of God’s punishment and hell. He argues that Jesus taught that God doesn’t repay evil for evil, and like God, we must love and forgive our enemies. Where Jesus mentions hell, it was to subvert that idea and replace it with a more loving conception of God. So, he says, it is inconsistent with God’s character to punish sin forever in hell.

Where does this leave Biblical authority?

He argues that Jesus, Paul and the writer of John’s letters and gospel all interpreted scripture according to their experience of God’s action in their lives. We see the same in the change of Peter’s attitude after the Spirit led him to meet with the Gentile Cornelius (Acts 10 & 11).

Thus, he argues (though I’m not sure I see the connection) that the “correct” reading of scripture is the one that leads us to God and to a loving life. We need to do this in community, and with the guidance of the Holy Spirit.

He argues that this “good news” focus is much more in tune with Jesus than a book focus. It aims to lead us to Jesus, who is “the way, the truth and the life” (John 14:6) rather than to some rigid, eternal ethical truth.

Assessment

I have tried to describe this book’s argument fairly and comprehensively. So, do I think Derek Flood is correct?

His discussion of the Old Testament isn’t novel. Many faithful christian (and other) scholars and writers have been coming to similar views in recent years:

- the early Old Testament describes a period when Abraham and his descendants were only just coming out of paganism, and still retained many pagan views about Yahweh as a tribal god;

- much of the “history” before king David is at least partly legendary, and the genocide in Joshua didn’t happen as described;

- thus the Old Testament speaks with many voices, and doesn’t represent the final revelation of God’s true character.

I honestly can’t see how any christian can, if they allow themselves to think this through with an open mind, support the idea that God really commanded genocide.

Things I can’t be comfortable with

I am sympathetic with many aspects of his discussion of the New Testament – they are similar to Anabaptist understandings of interpreting scripture through Jesus. But there are some areas where I feel Flood has either gone too far, or too fast – i.e. he hasn’t properly justified his conclusions, or may not have thought through thoroughly enough the implications of his argument:

- His main christian ethic is enemy love (“If the core teaching of Jesus is rooted in enemy love …” p 173). But while I think forgiveness is core, and enemy love and non-violence are very important aspects to Jesus’ teachings, I can’t think it is right to isolate them from other core teachings.

- His use of “by their fruits” as a criterion of judging and deciding on ethical questions is close to utilitarianism, a moral philosophy that has many attractions, but which suffers from the difficulty of predicting outcomes and of arriving at any objective criteria for balancing competing interests and effects.

- I think the implications for Biblical authority are not yet well worked out. If the Bible’s teachings can be so easily put aside in favour of our assessment of the outcomes of actions, it is hard to see what value scriptural teaching on ethics still has for us.

- Although he mentions the Holy Spirit, I don’t think the Spirit gets enough attention. Learning to be led by the Spirit into God’s truth for today as a community of believers is surely more important and more open than following an assessed trajectory.

- In common with much progressive christian thinking today, Flood seems to want to make everything “nice”. Of course I agree that God is love, and love must be our primary motivation. But the loving God has created a world in which there is much possibility of evil and suffering, and Jesus showed a tough and confronting love at times. I don’t think Flood takes enough account of this.

- Flood’s views on the atonement, only hinted at here, but fleshed out more in his book Healing the Gospel (which I haven’t read, only read about), are critical of penal substitutionary atonement. He says his view is Christus Victor, but it seems to me more like some form of the moral influence or example theories, which don’t seem to explain why, if Jesus’ death was not necessary, it shows love rather than foolishness. But perhaps this criticism is unfair since that isn’t the main subject of this book.

- The logic of his arguments leads to universalism (I think), a view which I wish was true, but think is probably not, and I think the conventional teaching on hell can be shown to be wrong directly from Jesus’ words, without arguing that Jesus only mentioned hell to subvert the idea.

- In the end, all this could easily lead a reader to think that Jesus isn’t as important as christians claim, and a non-violent humanist who loves his or her enemies would be just as acceptable to God as a faithful christian. Maybe they are, but we need to think hard about this.

I don’t claim to have a full and fair understanding of his views, and I don’t say he is wrong on these matters. But I do think they are areas of weakness that need to be more comprehensively addressed.

The bottom line

As the cover blurbs say, this is an important book that captures the christian zeitgeist (if that isn’t a contradiction in terms), leads the way into some new thinking, and opens up important conversations. I don’t think he has got it all right, but who has?

We can be thankful that these ideas are out there, and I wait with interest to see how the Holy Spirit leads God’s people in response.

Reblogged this on James' Ramblings.

For a more brief treatment of the same ideas as presented by Derek Flood, please see,

“Is God Violent, Or Nonviolent?” at

http://www.evangelicaluniversalist.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=6581

(which I have offered before).

Blessings.

Thanks for that link, it contains some good information. It addresses the first half of Flood’s book, regarding the change between the Old Testament and the New, but I don’t think it addresses Flood’s idea that we need change from the New until now, which you may or may not agree with.

I’ve read Flood’s book some time ago and am currently in the middle of Brian Zhand’s latest, “Sinners in the Hands of a Loving God” (which I highly recommend). I’m intrigued and sympathetic toward the “continuing arc” idea behind Flood’s book and I would tend to fall into the camp of agreeing with his assessment. In fact, in reading Zhand’s book, I kept thinking back to a lot of what Flood had to say so the timing of your review brought a smile to my face. Cheers!

Hi Kent, yes, there seems to be a growing movement toward the thinking of Zahnd, Flood, Boyd, etc. As usual, I can go halfway or more with what I’ve read of these guys, but not the whole way, yet at least. I think they all point up problems that conventional evangelical theology doesn’t address well, or makes too definite statements about, then replaces that with theology where they may be being too definite too. I think they all think we can know more than we can. But I certainly appreciate them all, and I’m glad you’re finding them helpful.

This seems to be an excellent review, at least as far as I can tell considering that I haven’t read Flood’s book or any of his thought. Being familiar with Greg Boyd’s and Brian Zhand’s similar offerings to this particular conversation about God, Jesus, and Violence, however, I greatly appreciate your sensitive and articulate presentation and analysis of Flood’s theology. I especially appreciate your humble and cautious criticisms of the weaknesses or theological problems with adopting his approach to the issue. Solving perceived theological problems while introducing worse problems into the thought and spiritual life of the church isn’t what I consider progress. Evolutionary conceptions of God as they are being revealed in “the spirit” within christian communities today as transcending the apostolic witness through scripture can only lead to new and different conceptions of God and the Gospel. There are very good reasons to be skeptical of much that is emerging today–test the spirits in light of the Spirit of Christ revealed to the apostles. When Christ returns he can revise and reform our understanding of God’s will for the future in any way he wills–that is not our job and we don’t have that authority.

Thanks. I wanted to give a fair outline of what he argues, plus express my support for much of it and my concerns or questions about significant other parts. Judging by your comments, and Kent’s, I may have struck a fair balance. Thanks.

I always enjoy your honest and thoughtful posts. This book has being on my wish list for a long, long time already. Hopefully I will get to read it eventually.

Thanks. I felt underwhelmed by the second half of the book when I read it, but when I went through it again to do the review it seemed to be a little more helpful. I certainly think it is important. I hope you find it more or less as I have described.

Unfortunately, even in the Epistles, and in the Book of Revelation, we can still see some mistaken conflation of God with Satan; that is, we can still see some idea of God being violent against people.

But we must read the entire Bible through the filter of love. The Scriptures are only part of a progressive revelation, reflective of the human mediators’ growing understanding of God’s true character. And that revelation is ever-increasing and never-ending.

Allow me to make an additional reading recommendation from my friend Richard Murray: his free ebook, _God versus Evil_, at

http://www.thegoodnessofgod.com/file/God-vs-Evil.pdf

In this book, Murray further addresses such intriguing questions as,

-DOES THE BIBLE SAY WE ARE TO “FEAR GOD WHO IS ABLE TO DESTROY BOTH BODY AND SOUL IN HELL?”

-WHO MURDERED ANANIAS AND SAPPHIRA?

-HOW DO WE TELL THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PAUL’S “PHILOSOPHY” AND PAUL’S “EPIPHANIES”?

-WHAT ABOUT ALL THE WRATH IN THE BOOK OF REVELATION?

Blessings.

Hi Kevin, thanks for your thoughts, and the link. That is a big effort for Richard to have written that book!

Obviously I am leaning towards the views you and Richard express. My concern though is that if we say that God is as loving as we can imagine, then it is difficult to explain the horrors and suffering in this world. Our theology has to be able to cope with the fact that God created this world and was willing to allow this level of suffering. That is a terrible and difficult fact to face. Somehow God’s love is tougher than our understanding of love is.

I’m still grappling with how to fit these different facts together. Thanks again for your input.

So, according to Kevin, “even in the Epistles, and in the Book of Revelation, we can still see some mistaken conflation of God with Satan; that is, we can still see some idea of God being violent against people.” Well, this appears to be the statement of someone with better insight into who God is than Jesus and those he called and empowered to witness to him. Presumably, you Kevin, are one of those authorized to bring us this new revelation you refer to by saying “scriptures are only part of a progressive revelation, reflective of the human mediators’ growing understanding of God’s true character. And that revelation is ever-increasing and never-ending.” Unfortunately, this kind of progression can lead people in the direction it did the German folk during the Nazi era. Progress can be a relative concept. As for me and mine, we’ll stick with the revelation authorized by Jesus.

RICHARD WORDEN WILSON: I believe God is completely nonviolent, and exclusively a unipolar Daddy of love, whether we believe it, or not.

UNKLEE: As to my theodicy, God is only about life—abundant life—not suffering and death. However, by His choice, he has apportioned authority to angels and men, thus limiting his sovereignty.

God has disallowed all evil through “the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world.” But we must each choose to receive Jesus and his gift for ourselves, individually.

Through his “divine exchange” at the cross (see Isaiah 53), Jesus has TAKEN our sin and suffering, and GIVEN us his righteousness and “shalom” (shalom being variously translated as “health,” “prosperity,” “safety,” “contentment,” “friendship,” and “peace”).

We are all now here together in this temporal classroom, but eventually every last one of us will choose the gift of Christ (most, when in the lake of fire), and graduate together to eternity. This is why God is indeed joyful and lighthearted: we all live happily ever after.

Blessings.

Please see, “Is God Violent, Or Nonviolent?” at

http://evangelicaluniversalist.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=14&t=6581

Reconsider Matthew 25:46, regarding the fate of the damned and of the saved. Jesus says,

“Then they will go away to eternal punishment but the righteous to eternal life.”

1. But the Greek word translated “eternal” (or “everlasting”) is aionios, and does NOT in fact mean “unending or everlasting in quantity of time.” Rather, aionios speaks to an “indeterminate age set by God alone.” This adjective is used to describe something within time, not outside time (that is, in eternity). Aionios is the adjective form of the Greek word aion, where we get our English word “eon” (age). Young’s Literal Translation for aionios is always “age-during.”

2. And the Greek word translated in this verse as “punishment” is kolasis, a term used to describe the pruning back of trees, to allow fuller and healthier growth. It is also used to describe corrective punishment, “inflicted in the interest of the sufferer.” (For vindictive, vengeful punishment, “inflicted in the interest of him who inflicts it, that he may obtain satisfaction,” the word timoria is used.)

Note: Many erroneously believe that if you deny that the punishment of this verse lasts forever, then you must also deny that the “eternal” life of the saved is unending. But that doesn’t follow, because this verse is dealing with life, or punishment, WITHIN TIME, during the final eon. However, eternity is outside time.

In 1 Cor. 15:20-28, we discover where time will come to its end, and eternity will begin. When the last person has repented in the lake of fire, the purpose of the Lake will be finished. It might take a long time, but “Love is patient.”

Each unsaved captive will gradually be unbound by Jesus to receive him, and to accept the invitation to come through the gates into the City (“On no day will its gates ever be shut” Rev 21:25), in order to take the free water of life offered there. Jesus shall lose none of all those God has given him: all are predestined for salvation; all, sooner or later, will believe. “In Christ ALL will be made alive” 1 Cor. 15 v. 22. And only “then comes THE END” v. 24. All Death will have been abolished (which would include the Second Death, The Lake of Fire) v. 26, and God will finally be “all in all” v. 28.

More blessings.

Hi Kevin,

I have visited that link before, and I am much in sympathy with what you say. But I feel we need to be careful, in our zeal, not to overstate the case, and not to oversimplify or be too definite where we don’t actually have certainty.

1. I certainly agree that “eternal” doesn’t necessarily mean “everlasting”, but “in or of the age to come”, but I’m not sure I can agree with your “something within time, not outside time (that is, in eternity)”. My understanding, always open to more, is that the Jews saw time as being divided into the present evil age, and the age to come, ushered in by the Messiah, when all wrongs would be righted and only good would prevail. I don’t think they had any concept of timeless eternity, and I’m not aware of any reason to subdivide the age to come into a temporal section and a non-temporal section.

2. And I’m not sure about your definitions of the different words used for punishment. My concordance shows that (1) there are quite a few different Hebrew and Greek words used for punish and punishment, (2) kolasis is only used three times If I have counted right) and (3) it doesn’t seem to carry the meaning you say – Bauer’s lexicon second edition gives meanings in the wider Greek literature of “long-continued torture”, “injury”, “divine retribution”, “eternal damnation” and something to be feared. I’m not a Greek scholar, but it seems that the Bible writers may not use the word exactly as you say.

3. I would love for universalism to be true and for your last paragraph to be true, and I know there are passages that suggest it. But there are, I believe, many more that suggest otherwise. (See my Hell – what does the Bible say? for more on this.) Again, I think your last paragraph says more than we can know.

So I think these matters are not as clearcut as you suggest, and we need more prayer and guidance from the Holy Spirit to discern the truth here. I think discussion like this is an important part of that.

UNKLEE, I think we all subjectively filter competing doctrinal ideas through our viewpoint of God’s true nature. I now see that He IS love (vs. “loving”), and this has opened up many new vistas for me.

Hi Kevin, yes I agree we all do that, we are human and that is our nature. But my concern is to try to allow the Holy Spirit to be the filter, not my own wishes.

I understand that God IS love, but I wonder whether our understanding of love is the same as his. Obviously the word has a basic meaning, but I wonder about the nuances. What if God’s love is tougher and more demanding than you and I would like to think it is?

In the end, we have to trust revelation, through the scriptures and through the Spirit. So while I recognise that the Bible gives us a gradually developing understanding of God, I am wary of just wiping out the New Testament understanding, which is the most developed we have in scripture. If we think we need to move forward from the NT, as Flood suggests (and which I agree is necessary in some things), I think we need the consensus of the Spirit rather than our subjective opinions. It is in hope of contributing to a recognition of the Spirit’s consensus that I write in this blog.

What do you think about that?

I think you and your blog are inexorably moving toward the recognition that God is always better than anyone has yet understood.

Thanks for the vote of confidence. I’m not sure about “inexorably”, as that would imply I/we knew exactly what was true, about this matter and others too. But I hope I am moving forwards in my understanding. Best wishes.