The story of Moses leading the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt in the second millennium BCE, across the desert and finally, a generation later, into the “Promised Land” of Canaan, is foundational to the Jewish people and nation, and to the Jewish faith.

The book of Exodus describes these epic events. God sending ten destructive “plagues” on Egypt until Pharaoh agrees to let the Israelites go. The first Passover meal. God parting the Red Sea to let them escape the pursuing Egyptian army. God giving the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai, plus laws that defined Jewish worship and communal life. And finally, of course, the Israelites taking control of the land, which they have claimed as theirs for three thousand years.

The story is important to christians to, for from it comes many New Testament allusions, including the beginning of the Eucharist or Lord’s Supper.

But did the story really happen in history? And what does it have to say to us today? Two books give some clear answers.

History?

Biblical archaeology used to try to demonstrate the historical truth of the Old Testament narratives. So-called “maximalists” still argue that the accounts, including the exodus, are more or less historical. But against this view are the “minimalists’, who tend to think that the Biblical accounts are doubtful, and the exodus stories totally unhistorical.

Most historians are less dogmatic, but since there is little archaeological evidence for nomadic peoples, especially fleeing slaves, there is little to go on.

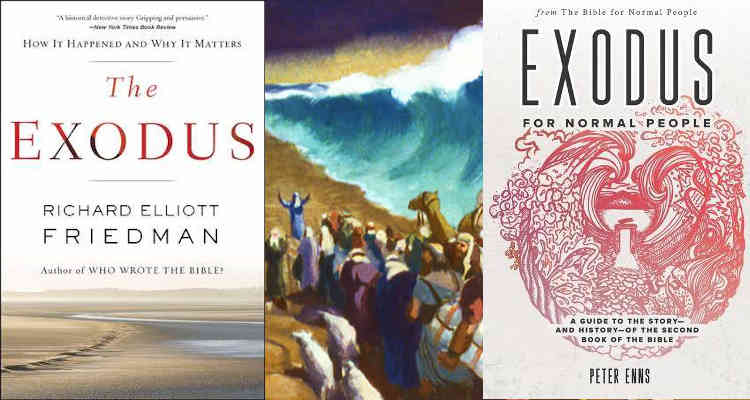

The Exodus by Richard Elliott Friedman provides some useful evidence that helps establish some middle ground. Friedman doesn’t believe 2 million Israelites, with miraculous support from Yahweh, made the journey. But he does offer evidence that a group of escaping slaves form the basis of the story we read.

The Levites

The Levites are the Israelite tribe that forms the Jewish priesthood. Friedman gives reasons to believe that the Levites had a strong connection to Egypt:

- the movement of people from Canaan down to Egypt, and back again, is historically accurate,

- the story of slavery is an unlikely invention, and the rescue from slavery is integral to the Jewish understanding of God (“I am the LORD your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt.”),

- some of the Israelites’ names are Egyptian in origin,

- different names are given for God in the different sources that make up the Old Testament, and these names fit best with the idea that the Levites brought the name Yahweh to Canaan,

- their religious practices (notably the tent of meeting and the ark of the covenant), appear to copy elements of Egyptian religious practices, and

- the DNA of modern Kohanin (those Levites who descend from Moses’ brother Aaron) is different to the rest of the Jews, whose DNA is similar to other descendants of the ancient Canaanites.

So, Friedman concludes, the 12 tribes of Israel were in Canaan all along, each tribe with its own defined area of land. The Levites came from Egypt, which explains why they don’t have their own defined tribal land. They brought the worship of Yahweh with them, and it eventually evolved to become the Jewish religion.

This view doesn’t settle the question of how much, or how little, of the story as we have it is historical, but it does provide a basis for a historical core.

Friedman also argues that the exodus story is the source of Jewish monotheism and the ethical concern for the stranger and alien (“because you were once aliens in Egypt”).

A christian understanding of Exodus?

Peter Enns’ book on Exodus answers some of the question raised by reading Friedman’s book.

Is the Exodus story historical?

It seems best to see it as “mythicised history”, meaning it has a historical core but most of the details are there to make a point rather than record accurate history.

How do we know the Bible story is mythicised history?

- Many details seem to be taken from other Middle Eastern legendary stories.

- The language and some anachronisms indicate that the text was given its final form centuries after the events portrayed

- Several parts of the narrative are recorded twice, sometimes with different details. They can’t both be right. It appears that different narrative traditions were passed down, and the final editors retained both traditions even though they are often inconsistent.

- There are many themes running through the book that have parallels in Genesis. It appears that the authors are promoting theological ideas rather than writing straight history.

What are the main themes?

- Yahweh is holy, powerful and the only god worthy of the Israelites’ worship.

- The Israelites are God’s chosen people with the task of showing Yahweh to surrounding nations.

- For this reason, the Israelites must live holy lives and worship Yahweh in the way he prescribed.

- The land of Canaan is promised to Israel.

What can christians learn from Exodus?

Although Exodus is mythicised history, we cannot really understand the Jewish religion (which was the religion of Jesus) without understanding Exodus. Some of the teachings may have been written into the story at a later date, but they are still part of the way God prepared for the coming of Jesus.

If we try to understand Exodus as literal history, we will miss what it is saying and end up with some ideas about God that are problematic (e.g. Yahweh’s anger and apparent disregard for human life). But if we see Genesis and Exodus as stories written to share truths about God and the world, we are closer to reading it as it was intended. And if we see it as a first step in an unfolding revelation, and therefore incomplete, we will (I believe) see it in a truer light.

What does this say about the Bible?

The conclusions from these two books would be troubling for a conservative christian. But they need not be.

We should judge the Bible for what it is, not for what our dogma or desires want it to be. The book of Exodus gives every appearance of being mythicised history, a reflection of a time when God’s revelation was far from complete. There is no reason why God couldn’t reveal himself through such a book. There is nothing to fear.

And this view helps us understand God better.

- God chose to reveal himself in a humble way, not through violent and spectacular events, but gradually, in history, and through imperfect people. CS Lewis says this process is “the greatest revelation of God’s true nature“.

- God is fully revealed in Jesus as a God of immense love for us. The Yahweh depicted in Exodus, killing innocent first born children, even trying to kill Moses, quick to anger, is not a true picture, but the first stage in a gradual revelation. A more or less pagan view of God is gradually purged of mistaken views. At first, CS Lewis says, God’s power is revealed and understood, then that he is the one true God. Only later do the Jews come to understand his “justice, then mercy, love, wisdom.“

None of this affects the miraculous elements of the story. Even if the exodus was only a smaller group of Levites, God could have used miraculous means to lead them – or he may not. But I personally find it difficult to believe that the destructive, murderous miracles were historical acts of God.

Two books worth reading

Both books are easy to read, light-hearted and humorous in places and well worth the time. Friedman’s book is more for those interested in the historical basis for the exodus. Enns’ book is more for christians who want to see the book of Exodus with new eyes.

Read more

I have written about the exodus from a historical perspective in The Exodus – what can we learn?