I don’t know about you, but when I read the Old Testament accounts of Joshua and the Israelites invading Canaan, I don’t have any picture of the geography or where the cities were located.

The matter is complicated by the fact that many people feel a lot is at stake. Believers generally want to find support for the Bible, and some unbelievers want to undermine it. Some Jews and Palestinians want to support their rival claims for the land.

So when I read the opinions of historians and archaeologists on whether these events were historical or legendary, I have little on which to base a judgment. I don’t think it’s the most important thing in the world, but it has been interesting to try to ferret out the truth, to read all sides of the question and try to come to an honest and true conclusion.

Geography and the Bible story

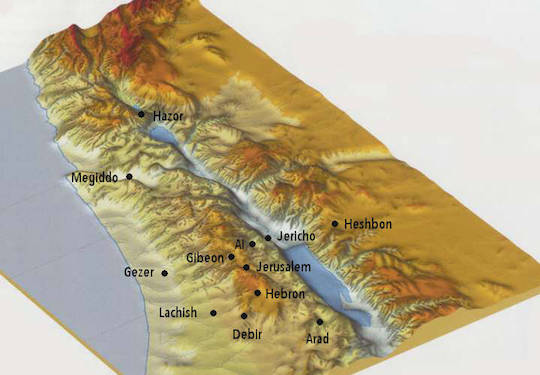

The land area known as Canaan in the late second millennium BCE included land on either side of the Jordan River, roughly where Israel, Palestine, Lebanon and Jordan are located today. There were fertile lowlands along the mediterranean in the west, with less fertile highlands in the centre and east, separated by the Jordan valley. The land was populated by diverse Semitic tribes, mostly living in small city states.

The Bible describes the Israelites entering Canaan from the south east, adjacent to the Dead Sea. After some fighting with tribes in the area of Moab, the Israelites crossed the Jordan and successfully attacked and destroyed the fortified cities of Jericho (near the Jordan) and Ai (in the hill country). God is portrayed as giving commands and help for both battles, and for most of those that follow.

The people of Gibeon tricked Joshua into a peace treaty, so their city was not destroyed, but Joshua moved on quickly to defeat armies and capture fortified cities (Makkedah, Libnah, Lachish, Eglon, Hebron and Debir) in the southern hill country. The Bible then records him heading to the far north (almost 200 km away) to capture and destroy the city of Hazor and capture several other cities also. In all, Joshua 12 lists 31 kings who were defeated, and Joshua 11 says (twice): “So Joshua took this entire land.”

Not so fast – a different story

But that isn’t the whole story. Later in the book of Joshua, it is clear that the more fertile coastal lowlands, and several other cities (e.g. Jerusalem, Gezer) had not been captured as claimed earlier. The following book of Judges tells of the different tribes having to subdue Canaanite cities in their allotted areas, including some previously said to have been conquered (e.g. Debir), and in some cases failing to do so. And Samuel and Kings report that some cities (e.g. Megiddo, Jerusalem) were not controlled by the Hebrews until several centuries later.

So the Bible recognises that the conquest was far from complete, despite the strong statements in Joshua. It is almost as if there are two different accounts, a more accurate one later in Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings, and an earlier “talked up” account in Joshua 1-11.

Archaeology and history

Dating

It isn’t clear what date should be given to the conquest stories in Joshua. The text of the Bible, when compared to Egyptian history, suggests a date around 1400 BCE. However most scholars these days believe that whatever the accuracy of the account in Joshua, it refers to a time around 1230-1190 BCE.

History

Up until about this time, which was the end of the Late Bronze Age, the two major powers in the Middle East were Egypt to the south and the Hittites in the north (in modern day Turkey). The boundary of their empires was in Syria, so Canaan had been controlled by Egypt. However the decades either side of 1200 BCE were times of turbulent change as these empires lost all their power, for reasons that are still debated.

Therefore the unrest described by the books of Joshua and Judges fits this time in history. But the more settled Egyptian control and protection in earlier times seems to rule out a major invasion around 1400, although it is quite possible that a smaller group of Semites entered Canaan around this time.

Archaeology

The archaeology also supports the idea that this was a chaotic time of change. Many of the cities mentioned in Joshua were indeed destroyed and often burnt, and many of them (Hazor, Lachish, Debir, Eglon, Bethel) can be dated to around this time. At Hazor, Canaanite figurines were destroyed and typically Israelite pottery began to appear after this time.

An inscription (the Merneptah stele) shows that a people group named Israel was living in Canaan in 1207 BCE. All this lends plausibility to the Bible account.

On the other hand, Ai was a ruin at this time (the name even means “ruin” and it was destroyed almost a millennium earlier) and Jericho was destroyed around 1550 BCE. It is possible that there were small (unfortified) villages on these sites at the end of the Late Bronze Age, but this hardly seems to support the Joshua account. Several other cities said to have been conquered (e.g. Gibeon, Arad, Heshbon) did not apparently exist at this time (though it is always possible that their location hasn’t been correctly determined).

Furthermore, archaeologists think that the cities which were destroyed at this time were not conquered at the same time, as described in Joshua 1-11, but perhaps over a period of half a century or more.

So the archaeology is difficult and more than one interpretation is possible. But it cannot be said to strongly support the account in Joshua 1-11.

Settlement and re-settlement

It seems that Canaan was more urbanised in the Late Bronze Age, but towards the end of the thirteenth century, there was a move away from cities to smaller villages and towns, many of them in previously unsettled areas, mainly in the hill country and the Negev to the south.

The Canaanites were thought to be agriculturalists living mostly in the fertile lowlands, and the pastoralist Israelites mainly settled in the hill country. But there is also evidence of sophisticated agricultural activity in the highlands, suggesting that some Canaanites from the lowlands may have moved up to new territory.

It therefore seems possible that there was initially less conflict than portrayed in Joshua 1-11, and more like a gradual assimilation of new peoples with sporadic fighting, perhaps more like that depicted in Judges.

DNA evidence

A number of different DNA studies show that modern day Jews, Palestinians, Bedouins and Druze are very close genetically. It is therefore argued that the ancient Israelites were not genetically distinguishable from the surrounding Canaanites, thus the Israelite nation resulted from gradual settlement and assimilation rather than conquest.

This argument can be found in many places, but I haven’t been able to find a reputable source that shows that the relationship of modern day populations is a good indicator of the relationship of ancient populations. Nevertheless, it is evidence, even if not definitive

So how accurate is the Joshua account?

We have seen that even other parts of the Bible throw doubt on the historicity of a rapid conquest under Joshua. When the archaeological, historical and DNA evidence is also considered, it seems impossible to accept that the account in Joshua 1-11 is completely historically true. Conservative christians and Jews, and maximalist historians argue for a higher degree of accuracy than I believe the evidence warrants.

But on the other hand, even most of the more sceptical historians accept that there are likely some factual memories behind the stories. Israel Finkelstein wrote: “there is no reason why the conquest narrative of the book of Joshua cannot also include folk memories and legends that commemorated this epoch-making historical transformation. They may offer is highly fragmentary glimpses of the violence …. the destruction of cities …. that clearly occurred.”

Many experts take a view between the extremes of minimalism and maximalism, based on the evidence. After all, Joshua describes the geography well, and maps out a plausible campaign of conquest. A number of cities were destroyed around this time, and new settlements begun, and people were indeed on the move. There was a people group named “Israel” in Canaan at the time. The written text is evidence, even if its accuracy must be questioned and we have to choose between different accounts.

So we are left with a range of views, and a layperson like me can only choose somewhere in the middle.

So what actually happened?

It is possible that Joshua invaded in 1400 BCE, but the Israelites didn’t continue to control the whole area and had to re-capture some cities around 1200 BCE. But the archaeological evidence, as it stands, makes this sequence of events unlikely.

We have reason to believe that some Semitic people escaped slavery in Egypt and travelled to Canaan. It seems likely that some Canaanites moved into the hill country from the lowlands or the Negev. And it is almost certain that some Canaanites where already living in the hill country and they weren’t all wiped out. So it seems likely that these three groups formed the genesis of the people who were later known as Jews.

The Bible accounts reflect this somewhat chaotic time and history. The stories in Judges and the second half of Joshua are closer to the reality of a combination of settlement, assimilation and conflict. The immigrants from Egypt possibly brought their belief in Yahweh with them, and this belief battled with the more pagan Canaanite beliefs and practices for centuries before finally winning out.

The more warlike accounts in Joshua 1-11 are almost certainly exaggerated, a practice not at all uncommon at the time, possibly to strengthen the beliefs and culture of Israel and its claim to the land.

We can probably regard the accounts as “fictionalised history” – original true stories and memories that have been re-told, crafted and exaggerated to make a point.

What is the value of the Biblical book of Joshua?

It seems likely that those who compiled and edited Joshua, probably long after the event, had theological and national interest more than historical. The book shows us those beliefs, and forms part of a literary and theological process that took pagan people from a polytheistic nature religion to the monotheism that Jesus was born into.

Joshua is early on in that process, and so its view of God is still very primitive. But it is nevertheless and important part of the journey of progressive revelation, as God begins to reveal himself as a powerful god who would later be recognised as the supreme creator. But there’s not much morality or compassion there yet.

This view of Joshua would be distressing to many christians. But I find it a relief to not have to believe that the God of Jesus really did order such wholesale, slaughter over and over again. And to know that while such slaughter did happen back then, it probably was not as severe and in such large numbers, as the Bible describes, because some of the cities didn’t exist then, or weren’t destroyed.

Treating the book of Joshua as fictionalised history does nothing to my belief or faith in Jesus, and it makes it easier to believe in God, because I don’t have to believe that he was ever warlike and unloving.

References

On this site:

The more sceptical view:

- The Bible Unearthed. Israel Finkelstein and Neil Silberman.

The moderate view:

- Back to Basics: A Holistic Approach to the Problem of the Emergence of Ancient Israel (AJ Frendo in In Search of Pre-Exilic Israel ed John Day)

- The History and Archaeology of the Book of Joshua and the Conquest/Settlement Period (JF Drinkard)

- The Iron Age (Amihal Mazar, in The Archaeology of Ancient Israel, Amnon Ben-Tor editor)

- History and Theology in Joshua and Judges (Dennis Bratcher).

Support for an earlier date and the Biblical account:

- The Dating of Hazor’s Destruction in Joshua 11 by way of Biblical, Archaeological, and Epigraphical Evidence (D Petrovich)

DNA evidence:

- Archaeogenetics of the Near East (Wikipedia)

- Blood Brothers: Palestinians and Jews Share Genetic Roots (Haaretz)

- Jewish and Middle Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes (MF Hammer, et al)

- Abraham’s Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora Populations Comprise Distinct Genetic Clusters with Shared Middle Eastern Ancestry (G Atzmon et al)

- The Origin of Palestinians and Their Genetic Relatedness With Other Mediterranean Populations (A Arnaiz-Villena et al)

Map: Free Bible Land Maps

Well, I think I can agree with you that we can ignore this narrative in terms of furthering our understanding of the nature of God, and treat it as just blurred history written sometime after the event.

In fact I think that the mention of God throughout the OT is simply an attempt by a certain side to claim that a mighty unseen being is on their side, in order to boost the morale of the troops and strike fear into the enemy.

This spurred a retaliatory effort by Muhammed later on to claim God as belonging to his people for the same reason of boosting morale and engendering feelings of ‘great and powerful friends’ in the sky.

Let’s face it, if God was on one side then that side would have won centuries ago. I believe that God’s true purpose is for all religions (and non religions) to unite in the name of the human race and work for the advancement of mankind.

That will probably involve putting all religion aside, but then you have probably gathered that I think that religion is an invention of man, not of God. That doesn’t prevent people praying to God for guidance and hopefully receiving an answer, but that is a personal communication that can take place without the need for a Book.

Excellent article! Very informative.

Hi “West”, I like your phrase “blurred history”, I think that sums it up quite well, and leaves plenty of scope for different conclusions about how blurred it is.

Yes, the Nobel prize poet wrote many years ago “If God’s on our side, then he’ll stop the next war.” But at the same time, I think he is for peace, but we don’t have as much of that as I’d like either. I think the only conclusion is that God often (not always) leaves us to live with the outcomes of the actions we, or others, have chosen.

But of course we disagree about your final paragraph. I am happy to put “religion” aside, but I do think Jesus tells us more about God than we can learn any other way. So we agree 4 paragraphs out of 5! 🙂

Thanks for your encouragement JWB!

One small criticism: Finkelstein usually isn’t considered a minimalist (this label usually applies to scholars like Thompson, Lemche, Davies, Cryer, etc.) and I’m not sure he’d consider himself one. Biblical minimalism is a rather specific label.

As a small fun fact, many scholars think that the Sea Peoples played an important role in bringing down the Middle Bronze Age empires. The later Philistines are often thought to descend from some of those peoples. Their language seems to resemble Anatolic and Greek languages in places, their pottery resembles Mycenaean pottery and their funeral practices were very different from neighbouring peoples’. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/07/bible-philistine-israelite-israel-ashkelon-discovery-burial-archaeology-sea-peoples/

It definitely isn’t a good indication of the population genetics in pre-exilic times. Jews and Palestinians for instance both descend from the people who lived there in (late) antiquity (so you’d expect both to descend from Judeans), and there are probably also Arab and European ancestors to both populations. And even then there may have been little genetic difference in the late second millennium between the early Israelites and (other?) Canaanites, because both groups would have been of West-Semitic origin and the Israelites, if they did have a major component from people who entered from Egypt, may still have been of Canaanite descent.

Is it mostly an internet argument?

Thanks for the info on Finkelstein. I thought I had seen him referred to as a minimalist, and he certainly is towards that end of the spectrum. How would you describe him?

Yes, I have read about the sea peoples, their possible origins and the demise in Egypt’s influence in Canaan, but I decided not to include anything on them in this post.

I’ve certainly seen several atheist or sceptical sites that used this argument (e.g. this one), but I think I’ve seen it in some apparently reputable papers or articles as well, that’s why I went searching for the basis of these claims. But I can’t think of any references right now, I’m sorry.

I’m not really sure; he is certainly closer to the minimalists than to the maximalists, but I don’t think there is an accepted label. I think I may have seen the term Low Chronology used for his views in general, but strictly speaking that only refers to the chronological amendments he proposed for linking Palestinian chronology with the rest of ANE chronology.

I’m not surprised that half-sciencey argument is current among online atheists, but it’s depressingly racist if you think about it. As if ethnicity is all about biology, and as if genetical circumstances stay the same forever!

Though I note that page refers to Israelites and Canaanites, not to modern groups. I’ll search whether I can find anything on ancient groups later.

I did a little more checking, and it seems some people have said Finkelstein is a minimalist, but he says he’s not. So I guess I should modify my text slightly. Thanks.

That’s all right, but I think most if not all minimalists would actually deny that there is any basis whatsoever to all stories in the books from Exodus to Judges – this sets Finkelstein well apart from minimalists. The minimalist position on the Hebrew Bible is that it was composed in the Persian period with an intention to make a land claim, only loosely based on earlier sources (that they claim cannot be identified any more). So it wouldn’t make much sense for them to accept that there are historical echoes in the invasion narrative.

Finkelstein isn’t too far from that view, but it is true that he isn’t hard line about it.

Dear UNCLE and IGNORANTIANESCIA!

Nice to talk to you again 🙂

I have begun reading a lot of N. T. Wright now. Books.

According to the Old Testament, though, I have still a hard time nailing it. I’m reading the whole bible, you see, and I think that in some places the historicity of the old testament seems to be important to the new testament.

I’m aware that the old testament uses litterary genres that are not all to be taken as history, but rather as a narrative, a metaphor, etc. In this view one can accept myths as being a vehicle of driving home theological points.

BUT: I do find places in the new testament where the historicity for the old testament seems important. For instance:

Romans 9

I speak the truth in Christ—I am not lying, my conscience confirms it through the Holy Spirit— I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were cursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my people, those of my own race, the people of Israel. Theirs is the adoption to sonship; theirs the divine glory, the covenants, the receiving of the law, the temple worship and the promises. Theirs are the patriarchs, and from them is traced the human ancestry of the Messiah, who is God over all, forever praised! Amen.

Doesn’t Paul presuppose the importance of Israel’s history?

The adoption of sonship, the tracing of the Messiah, because of ex.:

– the covenants.

– the law.

– the patriarchs.

But then I think:

* What about the covenants with Abraham – a man that possibly did not exist.

And with Moses – a man that possibly did not exist either.

* The law – that is in moral terms no different for that of older religions like buddhism. (Buddhism have even extended their love to animals!).

The patriarchs – many of them have perhaps never existed.

Isn’t Paul justifying Israel as being something special for the life and work of Christ … the problem being, though, that he builds on a history that just is NOT history? That has never happened?

I’m confused …

Regards

Thomas

Hi Thomas, nice to hear from you again. I think each of us has to work out what we think about these matters, but this is what I think.

1. My faith is in Jesus, because I think the NT evidence for him is very strong. Nothing in the OT really adds weight to that evidence, though it does help understand him better, so I would believe in Jesus if there was no OT, or I though it was all a fabrication. That is my fundamental starting point.

2. There are many views on the OT, and not all of them entail Moses, Abraham, etc not existing. There are actually very few scholars who would say they didn’t exist. Most would say we just can’t know, or that they may have existed but many of the stories about them are legendary or exaggerated. Some say, on the basis of the text (often the only evidence we have), that the stories are substantially true.

3. I personally hold to something like the middle ground – that they quite likely existed but the stories are often legendary or exaggerated. That is a position based on a realistic assessment of the evidence, and a degree of faith. It wouldn’t disturb me greatly if the truth was different.

4. I think what is important in the OT is the ideas, not necessarily historicity. Legends can teach and inform just as much as history can. So I don’t really mind what is history and what is legend, until we get to the NT where I think that history is crucially important. So I find it quite plausible that Jesus and the apostles could refer to people who were legendary as if they were real, just like a Star Wars fan might as “as Obi-Wan Kenobi said: ….”. But if, as I think, the characters were likely real, then even that problem fades.

I have said before that I think we can see this happening in other formative myths, and the example I use is Australian Aborigines. They have their powerful and formative “Dreaming stories” which guided their behaviour, their lives, their annual routines, their law, for millennia. There is plenty of factual and useful information in them, but how much of the stories is historical is uncertain – and unimportant.

So I think Paul was calling on his culture and tradition, probably thinking it was all true, but it doesn’t really matter either way (in my opinion).

Dear Uncle

Yes, that made som relief initially for me when I thought about it myself before reading your post. But then I thought about the following:

* The difference between using the legends as teaching vs. arguing that Israel was the chosen people since ancient times. How can they be chosen, if their legends were fabricated (very late in fact) to suit a political need?

* The way Paul seems to using a legend, PRESUPPOSING its historical reliability, and then using that assumption to defend and argue Israel’s status as a chosen people.

(I wouldn’t mind him using the legends as teaching, but affirming their historical reliability as a foundation for arguing for Israel’s chosen-ness since ancient times, at a time when the legends were not even invented – and Israel was not even a people! – confuses me).

But I have also myself found a possible solution to the problem I want to share:

* Perhaps Paul isn’t using the legends and the assumption of historical reliability to ARGUE for his theological points (as I first thought). Perhaps he is using them to ILLUSTRATE his theological points, (which in fact has the ressurection as the concrete foundation for argumentation).

A concrete example could be my quote from the earlier post:

Romans 9

I speak the truth in Christ—I am not lying, my conscience confirms it through the Holy Spirit— I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were cursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my people, those of my own race, the people of Israel. Theirs is the adoption to sonship; theirs the divine glory, the covenants, the receiving of the law, the temple worship and the promises. Theirs are the patriarchs, and from them is traced the human ancestry of the Messiah, who is God over all, forever praised! Amen.

In this case Paul could believe in the existence of the patriarchs. But it doesn’t matter, if they existed, because his THEOLOGICAL POINT is not about their existence and doesn’t need their existence to be true!

– His point is about Christ not being for the few who shared his near historical context (the jews/Israel). Christ is for everyone! In flesh, in humanness, in historical context, he was among the jews, talked to the jews, lived a jewish life. But he is for everyone. If this is the theologocial point it may seem ok that he is using the patriarchs (legends or not) as a ILLUSTRATION of his point – the point being that even though Jesus belonged to the jewish traditions (“having the patriarchs!”), Jesus is not confined to being Christ for Israel.

The same could go about Paul’s view on Adam. Even if Paul believed in a real, historical Adam, he doesn’t need a historical Adam to drive home a point. But he can still “use Adam” as an illustration to drive home a point. The argument lies somewhere else, Adam is only used as ILLUSTRATION. I’m thinking about:

Romans 5:

12 Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death came through sin, and so death spread to all because all have sinned— 13 sin was indeed in the world before the law, but sin is not reckoned when there is no law. 14 Yet death exercised dominion from Adam to Moses, even over those whose sins were not like the transgression of Adam, who is a type of the one who was to come.

15 But the free gift is not like the trespass. For if the many died through the one man’s trespass, much more surely have the grace of God and the free gift in the grace of the one man, Jesus Christ, abounded for the many. 16 And the free gift is not like the effect of the one man’s sin. For the judgment following one trespass brought condemnation, but the free gift following many trespasses brings justification. 17 If, because of the one man’s trespass, death exercised dominion through that one, much more surely will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness exercise dominion in life through the one man, Jesus Christ.

N. T. Wright (if I have understood him correctly) uses a metaphor where a statue is being broken, but then made better than it was to begin with. If this is the case, the point about Adam as an illustration is that death and life – Adam and Christ – isn’t balancing each other out as one perhaps would think. The new creation is much more than the state before the fall (the brokeness of the statue). That is quite a gift and more than we deserved. Adam vs. Christ is then used as an initial 1:1-illustration ADDING (through that illustration), that we in fact get more through Christ than we lost in Adam. We are not just getting rid of sin, we are getting way more than that. More than we deserve on our own merrits.

Well, I’m not even sure I understand what I myself write! I’m thinking … thinking … thinking … Hope I can figure it out – in my heart first and foremost. praying.

I have to read that one again, with Paul and N. T. Wright. And pray for understanding.

But my point is though, that Paul may believe in the traditions and the legends, but his use of them – and the belief that they are historically accurate – is not needed as an ARGUMENT for his theological point, but only as an ILLUSTRATION. In that way they do learn us something as you said in your post.

But all this has led me to read about ancient Israel. Because, if the legends are only legends, and made up much later than the age they point to, and even made up because of political reasons, how can they justify Israel being God’s chosen people since ancient times? If there is no Abraham, no Moses, no ancient covenants … why then believe that Israel is chosen since ancient times? Because of their imaginative storytelling much later???

Regards

Thomas

Hi Thomas, I think you’ve got a good handle on it this time (i.e. I agree with you!). I think this is the key:

We can see that Jesus and the apostles often used the OT texts in a different way to we would, for example:

In John 10:31-36 Jesus quotes from Psalm 82, taking it completely out of context. The Psalm sarcastically calls some kings of nearby nations “gods”, and then says God will nevertheless bring them down. Jesus changed the meaning, following the way Jewish rabbis at the time would argue.

The famous verse in Isaiah quoted to refer to the virgin birth was originally a prophecy of the timing of God’s rescue of Jerusalem – by the time a young woman would give birth, it would happen. The application to Jesus’ birth is again more of an illustration using a method of ancient Jewish interpretation sometimes called “midrash”, where if two passages used the same words, they could be connected even if there was no other obvious connection.

I can’t see why God couldn’t choose Israel and then reveal himself gradually, at first through myth, and later through history. It may even be (I wouldn’t know) that God gave initial revelation via myth to all sorts of people, but Israel was the people who responded.

Dear Uncle!

Thank you. I will have to read up on that midrash. It sounds illogical. But perhaps it shows that they know the status of the writings not necessarily being historical, as we would think about that term today?

About myths I have come up with 2 examples to illustrate what I mean:

1) Suppose I’m 37 and feel that I am some kind of failure in life, but still feeling that I have a purpose deep down. So I invent being visited by an old wise lady since I was 7 years old. Now, I invent it in the age of 37. But the story tells about a boy (me) 7 years old when I first got a visit by an old wise lady. Now, the story goes that the old wise lady visits me every year. When I’m 7 … 8 … 9 … and so forth, the whole way up to my 37’th birthday.

Suppose these stories all contain some wonderful narrative. Suppose one could learn a lot about human psychology, philiosophy and a way of life from these stories.

But now comes to category-shift:

Suppose a friend of mine believed that I really got visited. He says to his friend: Thomas is very speciel. He got visited by this old lady since his childhood. AND SHE IS GOING TO VISIT US TOO!

2) Suppose Denmark in 1850 made up stories about giants living in their country for 1 million years ago. These stories are again great narratives, we suppose. We learn something about culture and geology and so forth … And perhaps the story even go that these giants are asleep deep down below the surface of earth.

But now comes the category-shift:

Suppose a man from Australia thought: I will go visit Denmark. Perhaps I can dig in the surface and find a giant and share a cup of beer with him!

—

What I’m trying to say is. Israel made up (or were inspired) some myths around the time of their Babylonian exile. The myths point all the way back thousands of years to some humans that did not exist – say Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses. Still great narrative though. And divinely inspired. We can learn something from them WITHING THE NARRATIVE itself.

Now comes the category shift:

Paul talks about Israel having the Patriarchs (from thousands of years ago), and so Israel is special.

Jesus talks about Abraham, Isaac and Jacob eating and drinking in God’s Kingdom. But they never existed. The narrative with them in it was designed to teach us something, not to convey true information about their existence. But suddenly Jesus speaks about them being historically real persons that will come and eat and drink in God’s Kingdom.

So:

There’s a narrative we can learn from. But the category-shift is jumping out of the narrative and claim that the made-up-persons of it really exists, and that that in itself is a speciel thing that either gives status or that the persons will turn up again in the future.

It is going from the narrative itself – acknowleding it’s a narrative – with its great lessons … going from that to suddenly claiming that the narratives conveys true information about these persons (patriarchs) existence.

That’s what confuses me.

Do you understand what I mean?

So the narratives, great lessons! Knowing it’s a narrative.

But then the shift: Talking for granted that it conveys true historical information about the people in the story (i.e. the patriarchs).

Regards

Thomas

He’s similar when it comes to the reliability of texts about the pre-monarchic period, but I believe his views on the later period aren’t as extreme as the minimalists’.

Anyway, the minimalists do form an exception to this, which was what I meant with my previous post:

I think that replacing “even the most minimalist historians” with “even most (of the) sceptical historians” would do the trick.

Yes, I think you are right that there can be a difference in how minimalistic a scholar may be about Moses compared to say Solomon. I was thinking more about Moses & Joshua.

I’ll make the change you suggest. Thanks.

Hello again Thomas,

I think there are two ways that I think differently to what you describe here.

1. I think you may be a little too “black and white” when you say “But they never existed.” Some historians say that, but most do not. I think it is pretty clear that many myths and legends have some historical basis, even if quite small – see for example my post on Troy.

So I think Moses and Joshua and Abraham were probably real people, but many legends have grown up around them. We cannot know exactly what is factual and what is legendary. Even the flood story is probably based on a real flood in 3rd millennium BCE Sumer, but obviously not a worldwide flood.

2. You have looked at it from the point of view of the Jews- “Israel made up (or were inspired) some myths around the time of their Babylonian exile. The myths point all the way back thousands of years to some humans that did not exist”. But what if we looked at it from God’s viewpoint?

Perhaps God allowed the human race to develop by evolution. Then when humans have advanced enough, he starts to give them impressions of the numinous, the supernatural, and the first superstitious religions develop. One nation seems to grab hold of the ideas better than the others so he starts to send visions and prophets and visionaries, who lead this people into a new land and a new culture. He gradually refines their understanding using the stories they have developed themselves, which are partly historical and partly mythical. They start to respect him as a powerful God, the only creator. More stories, more prophets, and they get the message that he’s not just some tribal god who will look after them and kill their enemies, but a moral being who wants them to live justly and righteously. They pass the stories down, then write the stories down, still partly fact and partly myth. Finally they are ready, and he comes down to earth as a human to complete the picture they have been gradually getting of what he is like and what he expects of people.

It makes sense to to me, but there is no time when people sit down to write a myth, they just develop slowly and are written down after many centuries of word of mouth telling.

Does that help at all?

Dear Uncle

It is easy for me to accept the old testament being mostly myths and the new testament being mostly history.

But it is harder to accept that the new testament writers require the myths to be factual history for the constitution of faith.

i.e.

How to meet the patriarchs in God’s Kingdom if they don’t exist?

And what about Hebrews 11? To me that chapter seems to assume the myths of Abel, Noah, etc. to be historical facts – that is, historical facts that constitutes what (at least partly) faith in itself is.

It would be easier if the myths were regarded as myths. But hard when they – by the new testament writers – are required to be historical facts as a foundation for faith.

How else to understand the examples above?

But I have a feeling that I’m not getting my point fleshed out clearly(?).

Regards

Thomas

Hi Thomas,

I still think you may be seeing things in too black and white a way. Here’s my ideas for you to consider:

” the old testament being mostly myths and the new testament being mostly history”

I still think this is too strong a statement. Genesis 1-11 may be “mostly myth”, but we simply don’t know about the rest.

“it is harder to accept that the new testament writers require the myths to be factual history for the constitution of faith”

I don’t think we know what they “require”. I’m doubtful they had even considered the question. CS Lewis says it is an historical fallacy to try to determine which answer the ancients gave to a question they hadn’t even considered.

“How to meet the patriarchs in God’s Kingdom if they don’t exist?”

I don’t think we can say that they didn’t exist, and I personally think they probably did. It is the stories about them that may be legendary, not necessarily the persons themselves.

“And what about Hebrews 11? To me that chapter seems to assume the myths of Abel, Noah, etc. to be historical facts – that is, historical facts that constitutes what (at least partly) faith in itself is.”

I don’t think we know what assumption the author made, nor what categories were in his mind. I don’t think cultures respond to their founding myths in the way you say. For example, I think it would probably be crass to ask an Aboriginal Australian whether their Dreaming stories were historical or myth. So I think the NT writers could well write about people who were part of their founding stories without really thinking about the question of whether they, or the stories about them, were historical. I doubt they even had a term to mean what we mean by “historical”.

“How else to understand the examples above?”

I have suggested another way. Myth is not just fiction. It can be what we call “historical”, or it may not be, but it contains truth that is important for the culture, and the “historicity” of the story is secondary. But even if the NT writers did have a concept of historicity vs myth, and we now believe they were mistaken about which category that put these stories into, that shouldn’t prevent us from holding a different view today.

“But I have a feeling that I’m not getting my point fleshed out clearly(?).”

I’m sorry you feel frustrated by this. I think you haven’t fully picked up on what I am saying too. These are difficult thoughts and questions. I feel you are approaching this from the point of view of an educated postmodern anglo-saxon European, which I presume is what you are. But these stories were written by Bronze Age Middle Eastern priests and sages, and interpreted by first century Jews. They thought very differently to you and I, and if we are going to analyse what they write, we need to do it with an understanding of the vast differences in time, space, language, culture and education between them and us.

Dear Uncle

Thank you for trying and for your time 🙂

My dilemma is not whether the NT writers choose between myth vs history. If they would use myths (even if having no choose because theory worldview NOT containing myth vs history) to get across points, great. It is the way they make the myths fit the overall structure that in some cases leads to something very illogical. i.e. eating and drinking with mythical persons.

Imagine for a moment my earlier example of the old wise lady … If my friend’s faith was constituted of the lessons IN the narrative, great, no worry. If on the other hand it was based on him meeting the old wise lady some day, then the tension between fiction and facts would have been stretched to the breaking point.

Before continuing … Do you understand my point about that?

Regards

Thomas

Hi Thomas,

No worries about my time, I am enjoying discussing with you, just sorry I don’t seem to have the answers to your questions.

Yes, I understand your point about myth being OK, but looking forward to having a meal with Abraham is strange if he never existed. But I don’t have the same difficulty with this as you do, for reasons I have already said. To summarise:

1. My belief about Jesus and faith in him isn’t dependent on this. Therefore, at the very worst, this is just an unresolved “problem”, and there are many things in life, science, religion, that we cannot resolve.

2. I don’t concede that these characters didn’t exist. We have little or no evidence they existed apart from the OT, but equally we have no evidence that they didn’t exist. It is therefore most logical to accept that they probably existed because the little evidence we have (mostly the text) supports this. (It is different with some of the stories, where the evidence might sometimes suggest, e.g. with Joshua, that some stories are inaccurate.)

3. It is therefore quite possible that we will see these guys in the next life. But even if we don’t and the NT writers were mistaken and they never existed, what difference does it make? So those statements about seeing them at a great feast, etc, were a misunderstanding, thinking that mythical characters were real. It doesn’t actually change anything substantial for me.

So in your example of the old lady – my faith is NOT dependent on meeting a mythical character as you suggest in this example. If my faith was dependent on the historicity of Abraham, then I would have a problem, but my faith is dependent on Jesus and he is NOT mythical.

Does that help at all?

Well said, Uncle!

Thanks.

Dear Uncle

Great! I’m enjoying it too 🙂

First: Do you have some links to the history of ancient Israel? When I look at Wikipedia the patriarchs are described as likely having not existed … that’s how I read it at least.

—

Yesterday something happened – a possible shift in my understanding. I have read some reviews of N. T. Wright’s book “Scripture and the authority of God”. I think about buying that book.

Some quotes:

* “Inspiration” is a shorthand way of talking about the belief that by his Spirit God guided the very different writers and editors, so that the books they produced were the books God intended his people to have.

* When full allowance is made for the striking differences of genre and emphasis within scripture, we may propose that Israels sacred writings were the place where, and the mean by which, Israel discovered again and again who the true God was, and how his Kingdom-purposes were being taken forward.

And about Jesus:

* at the heart of his work lay the sense of bringing the story of scripture to its climax, and thereby offering to God the obedience through which the Kingdom would be accomplished.

And from a review:

the point about God’s authority is that the whole Bible is about God establishing his kingdom on earth as in heaven, completing (in other words) the project begun but aborted in Genesis 1–3. This is the big story that we must learn how to tell. It isn’t just about how to get saved, with some cosmology bolted onto the side. This is an organic story about God and the world. God’s authority is exercised not to give his people lots of true information, not even true information about how they get saved (though that comes en route). God’s authority, vested in Jesus the Messiah, is about God reclaiming his proper lordship over all creation. And the way God planned to rule over his creation from the start was through obedient humanity. The Bible’s witness to Jesus declares that he, the obedient Man, has done this. But the Bible is then the God-given equipment through which the followers of Jesus are themselves equipped to be obedient stewards, the royal priesthood, bringing that saving rule of God in Christ to the world.

—

And so, yesterday I thought: What if scriptures are how God is calling humans to obedience. Through myth and history in a great narrative. If I view the “difficult” passages though the lens of “this is how God is calling humans to obedience”, what will I find?

And so I did with some of the passages I had difficulty with. Take for instance a word from Matthew 8:

“Truly I tell you, I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith. 11 I say to you that many will come from the east and the west, and will take their places at the feast with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven. 12 But the subjects of the kingdom will be thrown outside, into the darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

Earlier – as you know – I thought: Hmm, Jesus seems to take Abraham as a historical being.

And perhaps Abraham is. But what if he isn’t? Is Jesus’ words falling to the ground, then?

No! The words seems to convey an understanding bypassing the historical-critical-rational thinking – how powerful. Through the lens of “God calling humans to obedience” Jesus is simply continuing the narrative in new ways (even if the narrative is partly or wholly fictional). He is calling Israel to obedience, telling them that even though the good news have come to them first and is giving life to their own old prophecies (which, even if not being historical, inspires the human soul’s understand of God), they are not sure of a place in the Kingdom. Abraham is in this way symbolic for Israels deep relatedness to the will of God – but it’s not enough to have this relatedness “in the flesh”; it’s not enough to have been the people that responded to God’s calling first – and having build up traditions on that response. They will have to keep up!

In this way the narrative is continued on another level.

Another example I have wrestled with is from Romans 4, where Abraham’s faith is described in contrast to the law.

A bit:

“Therefore, the promise comes by faith, so that it may be by grace and may be guaranteed to all Abraham’s offspring—not only to those who are of the law but also to those who have the faith of Abraham. He is the father of us all.”

I thought: Why should I care listening to a text about Abraham that perhaps has never existed? Why should I hear about the law and circumcision? What has that to do with me? Maybe both Abraham and Moses with his law are myths, so what has that to do with me?

– And I had to stop and just listen intuitively through the lens of: How can this text be seen as God’s call to humanity, leading them to obedience? Why hearing this about Abraham and his promise, Moses and his law, why?

– And then it simply came: The text is giving me a sense of “innocence”. Abraham got a promise, when the religion had not flowered into laws and circumcision and food rules, etc. He was – and his religion was – in a very innocent state. And even if he did not exist (which he may have, as you point out), the promise of a multiethnic family obviously did exist before Christ – and have come to its fruition when the word got out to all the world after the resurrection of Jesus! But my point: It started in innocence with this forefather and the promise given to him, and it has RETURNED to innocence (after moving through the beginning of fruition of the promise given). The circle is complete and innocence is again at the heart of our worship.

Even if Abraham and Moses are mythical, these myths – and the way Paul is USING them – seems to give an intuitive feel of that innocence christianity is meant to have. An innocence that is greater and more powerful than the way some religion are constituted by rules and laws and so forth.

Am I making any sense?

Regards

Thomas

Hi Thomas, I haven’t got much to offer you regarding OT history. Anything by Peter Enns is good, I think, and this book looks helpful for the Exodus. Wikipedia is fine, but it reflects the views of those who did the last edit, and so can be very questionable on contentious matters.

Regarding the rest of what you say, you are thinking more deeply about this than I am, and I think you have found a key when you say: “: What if scriptures are how God is calling humans to obedience. Through myth and history in a great narrative. If I view the “difficult” passages though the lens of “this is how God is calling humans to obedience”

There are few christians, even those who think the scriptures are historically factual in every detail, who think that giving factual information about history is its primary purpose. As John writes at the end of his gospel, the purpose is that we believe and follow Jesus. Sometimes the facts are very important – e.g. it is crucially (pun!) important that Jesus really lived, died and was resurrected. But sometimes the message can come better through something other than factual history – e.g the parables of the Good Samaritan or the Prodigal Son.

I’m not sure I understand your ideas on innocence, but I agree with the direction your thinking has gone here.

Let me say that I agree very much with our dear Uncle–Peter Enns is great on the OT. He also has a very good blog at http://www.peteenns.com/.

Dear Uncle and no-baggage

Thank you both for your time and support.

I am listening to Enns now and then. Have become a huge fan of Wright! I have his series, NT-commentaries. Haven’t looked the mentioned text up though … I’m taking it chronoligically.

I just felt that Paul is using one of the grand persons, forefather Abraham, to show us something about bare trust and a promise with no laws and regulations etc added unto it. There is some kind of nakedness or innocence about it, I sense. No division through circumcision either. It all comes back – all the way back – to father Abraham and his hope against all hope.

Regards

Thomas

Hi Thomas,

I’m glad you feel you are getting a handle on all this. It is difficult stuff, and I think we will always have questions. But getting to a point where we can be at peace is good.