This page in brief ….

The Old Testament of the Bible records the Israelite nation fleeing Egypt in the Late Bronze Age (somewhere between 1500 and 1200 BCE), conquering dozens of cities in Canaan and killing all their inhabitants – all at the command of their God, Yahweh. Critics of the Bible point to these events as a serious reason not to take the Bible, or the christian God, seriously, while most christians find the events and the commands troubling.

But did it happen this way? Did God really command such atrocities? I have examined the historical evidence in some detail, and come to the following conclusions:

- It appears that large-scale genocide didn’t occur. The evidence supports the idea that a small group of refugees from Egypt settled in Canaan and over several centuries assimilated with the local Canaanite population and established the nation of Israel. Warfare and killing did occur and many cities were destroyed or captured, but the incoming Israelites were not responsible for all this. The destruction was on a smaller scale than a literal understanding of Joshua 1-12 suggests.

- The Bible presents two different pictures of these events. Joshua 1-12 is an idealised, hyperbolic and not fully historical account of total destruction that needs to be understood in its cultural context. But the remainder of Joshua and the book of Judges shows that the Israelites only gained control gradually, with much less fighting and destruction. This second picture agrees with the archaeology.

- We can choose between two views of this part of the Bible. Despite the obvious inconsistencies in the text, we can hold to the accuracy of the Bible and paint a very unloving and harsh picture of God as commanding whatever level of killing occurred. Or we can accept that the Bible includes two different versions of events, contains exaggeration and legend, and reflects the beliefs of the time, and so attributes to God actions that God wouldn’t have approved of. The second option seems best for three reasons:

- The historical evidence shows that this part of the Bible is not always literally historical.

- It seems best to see the Bible as progressive revelation, with this being a very early stage in that process.

- It seems abominable to attribute these commands and actions to the God of Jesus, who spoke out against violence. Our preconceived doctrine of scripture shouldn’t lead us to defame God.

- Therefore it seems best to say that the genocide didn’t happen, nor did God command it.

Read on to see the evidence that led me to these conclusions.

Bible background

The Old Testament (Joshua 1-12) records Joshua leading the Israelites in conquering Canaan in a quick military campaign, destroying cities, killing the inhabitants and taking over the land. In several passages (Deuteronomy 7:1-5, 20:16-18) God is said to have commanded the wholesale slaughter of the inhabitants, because of their wickedness (e.g. Deuteronomy 9:5, 18:9-12).

How should we understanding these disturbing commands, which appear to amount to genocide? Evangelical christians justify the behaviour of God (Ref 10) but is this fair to God’s character and to history?

The Bible tells two different stories

It turns out that the Bible has two different stories about the Israelite settlement in the Promised Land – the complete conquest story and another story of slow conquest and assimilation.

Different commands

The commands to utterly destroy the Canaanites sit alongside other statements that God would drive out the Canaanites via “pestilence” (Exodus 23:27-31, Deuteronomy 7:20) or other means (Leviticus 18:24-28, 20:22-23), apparently meaning that the Israelites wouldn’t need to fight.

And while the commands to utterly wipe out seem to be absolute, in at least one place (Deuteronomy 7:22) God says the Israelite conquest should only be gradual so that the land wouldn’t revert back to a wild state because it was not being grazed.

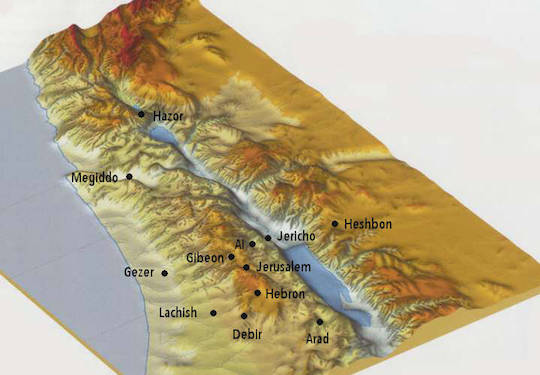

Approximate location of Canaanite cities.

Different outcomes

Joshua 1-12 describes a quick bloody campaign in which “Joshua subdued the whole region …. he left no survivors” (Joshua 10:40). Joshua 21:44 says the Israelites defeated all their enemies. And Joshua 12 lists more than 30 kings and their cities that he conquered.

But careful reading reveals another story, less obvious at first, but becoming clearer when we read the book of Judges.

- Despite the sweeping claims of total conquest, Joshua 1-12 actually describes the conquest of only some of the cities (e.g. Jericho, Ai, Hazor, Lachish), and makes clear that other cities (e.g. Jerusalem, Gezer, Megiddo) were not actually captured at that time.

- Joshua 13:2-6 lists several areas not conquered, and 18:1-3 seems to describe Joshua urging the Israelites to take possession of the land allotted to them.

- Other parts of Joshua show that some campaigns were not successful and many cities remained unconquered, for example:

- Geshur and Maacath in 13:13

- Jerusalem in 15:63

- Gezer in 16:10

- Taanach, Megiddo & Dor in 19:47-48

- The books of Judges, Samuel and Kings show that some of these and other cities remained occupied until much later, for example:

- Jerusalem in Judges 1:21-22 & 2 Samuel 5:6-7

- Gezer in Judges 1:28-29 & 1 Kings 9:16ff

- Taanach, Megiddo & Dor in Judges 1:27

- Debir in Judges 1:11-13

- Hebron in Judges 1:20

- Joshua 10:20 says that after the Israelites attacked some Canaanites in the open country, some of the survivors reached the safety of their fortified cities, implying that these cities were not captured, and again showing that the conquest was far from complete.

- And in Joshua 15:63, it says clearly that Israelites and Jebusites (one of the Canaanite tribes) lived together in Jerusalem, apparently peacefully. The two groups assimilated in some places.

So the Bible accounts, taken literally, tell contradictory stories which cannot be easily resolved, about at least nine cities or towns, as well as the campaign as a whole. We cannot simply accept the total conquest story and ignore the other accounts. We need to understand the Biblical text as a whole. The obvious next step is to see whether archaeology can resolve the difficulties.

The story from archaeology and history

Extensive archaeological studies have been carried out all over Israel, including many of the cities where we have contradictory stories. In addition, historical accounts of events at this time, from the viewpoint of other nations, are also available.

Some christians are unwilling to allow secular archaeology and history any part in interpreting the Bible, but in this case we have no real choice. When the Bible tells two stories, we need some external source to resolve which story is more correct.

The Exodus from Egypt

There is reasonable external evidence that some of the people who became the nation of Israel came to Canaan from Egypt (Ref 3).

- There is evidence that Semitic peoples, such as the Israelites, did often seek refuge in Egypt when drought or conflict affected their land.

- Several names in the exodus story (including Moses, apparently), and several religious practices (including the design of the temple and monotheism itself) appear to have Egyptian origins.

- DNA evidence suggests that the Levites (the tribe entrusted with the religious ceremonies in Israel) had an Egyptian origin.

- However there is no evidence that a number as large as the Biblical 2 million could have made this journey together, and logistics and archaeology suggest the number was much smaller. However it is possible that there were several Semitic groups which made the journey over a period of time.

The Israelite settlement in Canaan

Timing

Scholars are uncertain when the Joshua conquest could have taken place. The date favoured by some Biblical scholars is about 1450 BCE, but archaeologists and historians prefer a date closer to 1250 BCE (Refs 1, 2). Perhaps there were several migrations and the Joshua accounts are conflated.

Population

Archaeology suggests that the population of Canaan fluctuated considerably in the Bronze Age. Most estimates are in the range of 50,000 (perhaps before the Israelite settlement) to 150,000 (Refs 1 & 2). One estimate is around 600,000 (Ref 13), but few accept such a high figure. Whatever is the best estimate, we can say almost certainly that 2 million people never settled in the land at this time, and Joshua seems to be exaggerated and inaccurate at this point.

Archaeology and the destruction of cities

Turmoil and change

This was a time of turmoil. Egypt had controlled Canaan, but when Egyptian influence waned, it left a power vacuum and many different cities and tribes fought for power and land. Many cities and villages were destroyed at this time, although probably over a longer period than envisaged in Joshua, and possibly by armies other than Joshua’s.

Artefacts found in the remains of cities (e.g. pottery and religious figures) and a few texts (some on stone) show evidence of change, from Egyptian occupation and Canaanite culture to a mixed Israelite, Canaanite and sometimes Philistine culture.

Not so fast ….

However there is significant archaeological evidence against the rapid conquest story of Joshua.

- Several cities said to be destroyed by Joshua appear to have been destroyed centuries before – Ai almost a millennium earlier and Jericho in about 1550 BCE. If these places existed at the time of Joshua, they would only have been small settlements, not the cities that Joshua describes.

- Other cities mentioned in Joshua apparently weren’t established until later (e.g. Gibeon, Arad, Heshbon).

- Others (e.g. Jerusalem, Megiddo) remained unconquered by the Israelites until much later, just as the second story of Joshua and Judges describes.

Even many conservative scholars (Ref 5) accept that the Israelite entry into Canaan was not as destructive and rapid as portrayed in Joshua, but “involved several processes rather than a singular event.” It is widely accepted that Joshua is hyperbolic, in that several of the locations identified as cities were at most small settlements, and the destruction was not as complete as portrayed.

We can say almost certainly that while significant fighting occurred, often consistent with Joshua, the conquest described in Joshua didn’t happen literally as recorded there (Ref 1). There was no wholesale genocide.

Other evidence of gradual assimilation

Israel existed

An inscription (the Merneptah stele) provides good evidence that a nation known as Israel was in existence at the end of this tumultuous period (Ref 4).

Artefacts

Artefacts found in the remains of cities show that many Canaanites remained in their cities or were displaced to nearby rural areas, and newcomers were gradually assimilated over time.

DNA

DNA evidence suggests that modern day Palestinians and Lebanese are descended (in part) from Canaanites, as are modern day Jews. The Canaanites were definitely not all wiped out.

Understanding the Biblical text

The conventional Protestant understanding (e.g. Ref 10) is that the Biblical text is accurate (some say inerrant) and portrays real events commanded by God. The extreme action to exterminate all the Canaanites was justified because they were abominably evil (child sacrifice, ritual prostitution, etc) and that evil would contaminate God’s chosen people.

But there are significant problems with this explanation.

The Bible’s two stories

It is hard to see how this view can be maintained when Joshua and Judges contain two very different accounts, side-by-side, and sometimes interwoven.

Archaeology and history say otherwise

As we have seen, the history and archaeology suggest that the Joshua stories are not all literal history, but at the least exaggerated. The claims of total conquest reflect the situation several centuries later when the whole land was Israelite.

Hyperbolic language

Experts agree that the accounts, and likely the commands too, were written in hyperbolic language as was common at the time, and would never have been understood at the time as literal commands and accounts.

Were the Canaanites so evil?

There is no evidence that the Canaanites were any worse than other nations at the time. Child sacrifice and ritual prostitution were not uncommon (even the Bible contains the story of Abraham almost sacrificing his son Isaac).

Conclusion

It therefore seems best to consider the Biblical text as not fully historical (at least) and probably highly legendary. There is no in principle reason why God couldn’t reveal himself through legendary material.

What probably happened

Joshua 1-12 seems to present an idealised picture, and experts generally believe Judges better reflects the historical reality.

It seems likely that a group from Egypt entered Canaan around 1250 BCE and over a period of a century or more gained a place for themselves by both fighting and assimilating (as described in Judges). The resulting mix of original Canaanites, the immigrants from Egypt and other newcomers fleeing fighting on the coastal plains, coalesced into the nations of Judah and Israel in the hill country of Canaan.

The group from Egypt perhaps brought new religious ideas which competed with the Canaanite paganism and eventually became Jewish monotheism. It is quite possible that God used such means to reveal himself.

The Joshua stories seem to be based on facts, but much exaggerated, idealised and “talked up”, as was common at the time, to justify Jewish claims to the land. But in reality there appears to have been no genocide.

Philosophical and moral issues

Christians use various arguments to try to justify God’s supposed actions, but they are all unconvincing (to me), and several arguments undermine the idea that a good God could command genocide.

1. “It wasn’t really genocide.”

The UN defines genocide as “the deliberate killing of a large group of people, especially those of a particular nation or ethnic group.” If it happened or was commanded, it was genocide.

2. “The Canaanites were abominably evil and had been given many opportunities to repent. They deserved their just punishment.”

Most scholars believe they were not particularly worse than other nations who had similar practices, and who were never punished like this. And it was hardly just to punish those among the Canaanites who were too young or powerless to be considered responsible.

3. “It wasn’t so bad because the children were innocent and went straight to heaven.”

We don’t know whether the children went straight to heaven. Those who believe in the doctrine of Original Sin apparently believe no-one is innocent and thus without Jesus it seems, to be consistent, they must believe the children went to hell. Only those who don’t believe in the usual form of original sin can really believe the children were innocent.

But if the argument was true, why wouldn’t we kill all our children today (as one poor woman did) because that would ensure the greater good of their eternal future? No-one would suggest that this action would be justified today, so how could it have been back then?

4. Would you kill children today if you believed God had commanded you to?

I hope no christian ever would do so (though there are cases, e.g. the Rwanda genocide, when christians did do this). But if all the Bible is true, why would it be possible for God to command killing then but not now? If someone thought God had called them to kill today, we would (rightly) regard that person as having a mental illness.

So, could God have commanded these killings?

In the light of all that I have examined, there are four reasons why I think God did not command genocide, or even killing.

- We have seen that the accounts in Joshua present two different stories that at many points are not compatible. This part of the Bible cannot be seen as totally literal or historically accurate, but is hyperbolic. We have seen that the “commands” were inconsistent too, so it seems likely that they were also hyperbolic and not historical.

- The archaeology supports the Israelites’ gradual conquest and assimilation into Canaan, with less destruction and no genocide. The extreme language used in the “commands” and the reports is typical of that used by other nations, even in cases where we know that the massacres didn’t actually happen as claimed. So it seems that the rapid conquest story was Israelite propaganda.

- This all fits with a consistent view of the Bible as a whole (as held, for example, by CS Lewis), that God began with a pagan people and gradually revealed his greater truths to them. This was at a very early stage in that process, when God was still seen by them as their own tribal god, very little different to the tribal gods of the surrounding nations.

- As a christian, I believe the full revelation of God’s character is seen in Jesus, who was opposed to violence. It is inconceivable to me that Jesus would have given such commands or approved of such actions. It is more consistent to disbelieve the traditional view of the Bible as inerrant history than to believe God would order violent and unloving acts.

Conclusions

- It appears that large-scale genocide didn’t occur. The evidence supports the idea that a small group of refugees from Egypt settled in Canaan and over several centuries assimilated with the local Canaanite population and established the nation of Israel. Warfare and killing did occur and many cities were destroyed or captured, but the incoming Israelites were not responsible for all this. The destruction was on a smaller scale than a literal understanding of Joshua 1-12 suggests.

- The Bible presents two different pictures of these events. Joshua 1-12 is an idealised, hyperbolic and not fully historical account of total destruction that needs to be understood in its cultural context. But the remainder of Joshua and the book of Judges shows that the Israelites only gained control gradually, with much less fighting and destruction. This second picture agrees with the archaeology.

- We can choose between two views of this part of the Bible. Despite the obvious inconsistencies in the text, we can hold to the accuracy of the Bible and paint a very unloving and harsh picture of God as commanding whatever level of killing occurred. Or we can accept that the Bible includes two different versions of events, contains exaggeration and legend, and reflects the beliefs of the time, and so attributes to God actions that God wouldn’t have approved of. The second option seems best for three reasons:

- The historical evidence shows that this part of the Bible is not always literally historical.

- It seems best to see the Bible as progressive revelation, with this being a very early stage in that process.

- It seems abominable to attribute these commands and actions to the God of Jesus, who spoke out against violence. Our preconceived doctrine of scripture shouldn’t lead us to defame God.

- Therefore it seems best to say that the genocide didn’t happen, nor did God command it.

References

- Beyond the Texts. An Archaeological Portrait of Ancient Israel and Judah. William Dever

- The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the origin of its sacred texts. Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman

- The Exodus in Archaeology and Text. Richard Elliott Friedman

- Ancient Israel in Egypt and the Exodus. Biblical Archaeology Society

- Enter Joshua. John Monson. In Do Historical Matters Matter to Faith by J Hoffmeier & D Magary.

- The best way of getting out of the whole Canaanite genocide thing, and it comes right from the Bible (but you may not like it). Peter Enns

- The Canaanites weren’t the “worst sinners ever”: engaging Copan and Flannagan on Canaanite extermination. Peter Enns

- History and Theology in Joshua and Judges. Dennis Bratcher

- Bible says Canaanites were wiped out by Israelites but scientists just found their descendants living in Lebanon. Ian Johnston

- The Canaanites: Genocide or Judgment?. Greg Koukl.

- Did the Exodus really happen?. The Way?

- Joshua and the conquest of Canaan – what’s history, what’s legend and what’s unknown. The Way?

- A demographic analysis of late bronze age Canaan: ancient population estimates and insights through archaeology. Titus Michael Kennedy

Read more on this site

- Did the Exodus really happen?

- Joshua and the conquest of Canaan – what’s history, what’s legend and what’s unknown

- CS Lewis on the Bible, history and myth

- What the scholars tell us about the Old Testament

Graphic: Free Bible Images. This graphic shows the inhabitants of the city of Ai chasing the Israelites after an unsuccessful attack. There is some doubt about whether Ai actually existed at the time of Joshua, and the graphic may be anachronistic, as it appears to show the Canaanite soldiers wearing iron helmets, whereas this was still the Bronze Age, and neither the Canaanites nor the Israelites had iron weapons at this time.

Map from Free Bible Land Maps.