Last week Fariborz Karami committed suicide. And I don’t think many Australians noticed.

He was just 26 years old, and he had been held behind bars for 5 years without any hope of safe release. His mental health had been deteriorating for years.

But I don’t think many Australians cared.

Worse still, I don’t think many christians cared.

Fariborz Karami’s story

Fariborz Karami’s story

Karami’s story is told in this Guardian article (Deaths in offshore detention: the faces of the people who have died in Australia’s care). He grew up as a “member of Iran’s Kurdish ethnic minority, which faces systematic persecution in that country, he had been kidnapped as a 10-year-old boy and held for three months, threatened every day he would be killed.”

Five years ago he sought asylum in Australia, but his claim for protection wasn’t recognised, and he, his wife, mother and brother have been held in off-shore detention ever since.

It had been obvious for several years that his mental health was deteriorating. Over and again he sought psychiatric help, and psychiatrists said he was “severely traumatised”. But as his time in detention stretched on with no real hope of re-settlement, he sank into despair and depression, became suicidal, and eventually took his own life in his tent at the Manus Island detention Centre.

Twelve tragic deaths

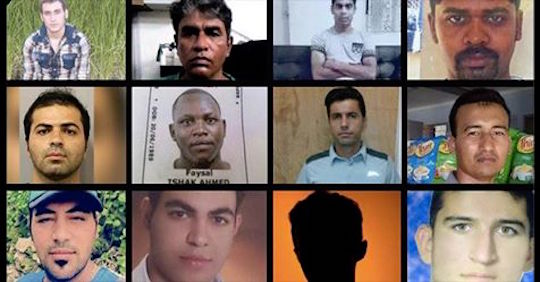

Karami’s death makes a dozen men, seeking refuge, who have died in Australia’s detention centres. Three have suicided, others have been murdered, died from accidents or illnesses, some from medical neglect.

It’s not a simple problem

There are apparently 68 million displaced people in the world today, almost three times Australia’s population. About a third of these are refugees, and about 3 million these are actively seeking asylum in another country at any time. Australia receives only a small percentage of these asylum-seekers.

Knowing how to respond to this crisis is an intractable problem. No country wants to be swamped with poor immigrants who may strain infrastructure, resources or public tolerance.

When a previous Australian Government humanised its procedures for dealing with those seeking asylum, the numbers of those seeking asylum rose dramatically. Since Australia toughened its rules, the numbers have dropped.

So no-one, certainly not me, thinks there are easy solutions to the problem.

Tough decisions may have to be made. Innovative solutions may be required.

But here I want to talk about attitudes.

Acting tough

Australia’s policy has been to be tough on those seeking asylum to discourage others from making the unsafe journey by boat and landing on our shores, asking us to act in conformity with the UN refugee convention which requires us to give protection to those with legitimate fears of persecution, and not to treat them badly.

Instead, Australia has breached several of the requirements of the convention by refusing the pleas of genuine refugees, keeping them in indefinite detention, and effectively expelling them from Australia by placing them in detention centres in other countries.

This is often presented as “being tough on people smugglers”, when in reality it is being tough on traumatised human beings like poor Karami. As one former detention centre manager used to say, his job was to make the camp a worse place to be than where the refugees had come from. (He resigned as a result.)

So it has become a political necessity to present a “tough” stance on refugees, first to please the right wing commentators and newspapers, but also to present an unmoving and unrelenting image to the electors.

For example, another asylum seeker is dying of cancer (Dying Nauru refugee speaks out as Muslim leaders plead for transfer), Australia refuses to provide him with palliative care in Australia, despite pleas by 2000 doctors and many othewrs, but prefers him to die with less care in detention. This is just one in a line of many similar cases of mentally and physically ill detainees being refused humane treatment.

So even when tragic events happen, like the murder of Reza Barati in 2014, the trauma experienced by children in detention, or the suicide of Karami, politicians and sympathetic media present a tough image, showing no remorse, no sadness, about the people so badly affected by our detention policy of neglect.

This deeply disturbs me.

Jesus said ….

It isn’t lost on those wanting Australia to adopt a more humane stance that Jesus had some very clear statements on how we treat people, including: “As much as you cared for (or didn’t care for) these people in need, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:31-46, my paraphrase).

And so christians who support the tough stance on deterring requests for asylum via inhumane treatment face a difficulty. Practical politics (or is it just the selfishness of the privileged?) says to be tough, but Jesus says to be loving and caring.

Have we really fallen this far?

Whatever political solution we believe is “right”, we are still required by Jesus to be compassionate. But our Government, including the last two parliamentarians charged with the responsibility of dealing with refugees who claim to be christians, shows no compassion, no regret, no humanity. They have to act tough or they will be seen as weak.

And here’s what gets to me.

So many christians are following their lead, and showing no compassion, no humanity. Instead of seeing these poor people as victims of oppression and even genocide (sometimes sparked by wars and policies that we instigated) who we should want to care for, even if we cannot, they see them as threats to our privileged way of life and therefore not deserving of being treated humanely.

And so christians who claim to follow Jesus have learnt to be inhumane, to lack any semblance of compassion. Somehow even the very worst behaviour is acceptable.

Have we really fallen this far?

Surely we should be in tears for these poor victims, even if we think we have no recourse but to have tough policies. Does Jesus not weep again?

May God have mercy on us all.

Top graphic: The faces of 12 asylum seekers who have died while in Australian immigration detention outside Australia in the past 5 years (graphic from the Guardian). Fariborz Karami is in the top left corner, Reza Barati at the bottom right.

Photo of Fariborz Karami from the Supporting Asylum Seekers Sydney Facebook page

You are right, it’s a tough problem . Governments refused reasonable proposals like the Malaysian people swap for crass political reasons. The Labor party is too scared to act because the Libs will bring out the “opening the floodgates” pejorative.

I think that there should be a maximum time that genuine refugees can be held before release. Enough to deter people smugglers but not so much as to cause mental health problems. People who are ill should receive proper medical attention.

There is a better way to do things than what we are doing now.

The current Minister is a disgusting person in more ways than one. He would make a good mate for Donald Trump.

I’m not an Australian and have never been in your country. I was inclined after looking at the teaser (via MennoNerds) to just move on. Chalk it up to compassion fatigue. But I do care about the death of Fariborz, and the deaths of those others who are despairing in similar circumstances. I’m an immigration lawyer in the United States, and we’re dealing with a very comparable situation now on our southern border. What we as Christians need to do, in addition to showing and advocating for compassion, is also demonstrate to the hard-liners that we understand the problems they are trying to confront. This may not help in the short term, but compassion can never be the whole answer to the dilemma because it will be perceived as selective compassion (e.g. what about your neighbors whose lives are affected by an illegal influx?). Our problems in the modern area may be somewhat different from the problems of welcoming the stranger and refugee as they existed in biblical times. I’m envisioning a whole new line of conscientization and advocacy which addresses the root problems of the movements of people that are sending people’s to Australia’s shores and America’s borders. Way more complex, way less manageable, way less timely. In the meantime, I mourn this suicide, and any talk of God seems too facile.

Hi “West”, nice to hear from you again. Yes, I agree with your thought that we need to find ways to deal with the likely flood of refugees and would-be immigrants without such inhumane treatment. I think I will post again on possible alternative policies. But my focus here was the more gut level revulsion at how easily we have come to accept treating people inhumanly and inhumanely. It isn’t so long ago (I believe) that most Australians would have revolted against what we now accept. I don’t feel my post fully expressed this thought well enough, though the title said it.

I don’t watch the commercial media but I would guess that Karami’s death would attract very little mention. Even on the ABC there is no mention. A search for “Karami suicide” only brought up The Guardian as a mainstream media outlet that presented the story.

The media seems to either not care or has been bludgeoned into silence by the government.

Hi Bruce, thanks for reading and deciding to comment. I appreciate input from someone with your experience.

I think this comment of yours is a very good insight: “[we need to] demonstrate to the hard-liners that we understand the problems they are trying to confront”. In the end, all governments have to make decisions, and those of us with compassion for the asylum-seekers must be able to offer a good way forward.

I agree too with your idea that we need to address ” the root problems of the movements of people that are sending peoples to Australia’s shores and America’s borders.” Trouble is, one of the root problems is global inequality – most refugees, as well as escaping persecution, want to make a better life for themselves so they look to the richer countries like ours. And we also know that our wealth has sometimes come via the exploitation of cheap labour and resources in poorer countries as well as harm to our indigenous people. Another important cause is warfare, often over scarce resources, and again inequality is a contributor. So I think addressing root causes might mean us wealthy western countries giving up some of our wealth and privilege.

I’d be interested in your ideas on causes and ways to address them.

But beyond all that, I feel we as a people have lost our compassion and have become hard-hearted and selfish, which christians at least should be very concerned about. That was the main point of my post. And if we have lost our compassion, we have also lost most of the incentive to find a better solution.

“The media seems to either not care or has been bludgeoned into silence by the government.”

I think much of the media is in the hands of right wing owners. I’m thinking especially of the Murdoch press. So I think many of them do care, but not to care for the refugees, but to care for their own wealth and the type of right wing society they want to see.

I had no idea that this was going on. The international media only really focuses on what’s going on in America at the moment. As someone who wishes to immigrate for the sake of work, safety and education I can (in a small way) somewhat relate to the frustration of just how difficult it is to get into a 1st world country and the sense that you are not really wanted there.

I don’t wonder you didn’t know because the total numbers are probably smaller than other refugee movements around the world, and both sides of politics here have similar policies, so the opposition is able to get less of a hearing. I don’t think we can blame countries from putting some limits on immigration, but how they do it is the issue I think.

I can (in a small way) somewhat relate to the frustration of just how difficult it is to get into a 1st world country and the sense that you are not really wanted there.

If you qualify for a visa to Australia via a points system relating to your skill set and the demand for your skills then you are wanted and needed.

People who turn up without going through the formalities are the ones being marginalised by most but not all political parties here because they know that an “open border” policy is political death in the electorate.

It is definitely a sad situation. But there is no easy solution. The best solutions is to try to help people in countries they live in (or close to them) so they can continue to live in the culture they prefer. Sadly we do not have infinite resources. And it is also sad that often it is questionable whether the leaders of these countries can be trusted to even deliver the aid we send. Of course that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do anything in the meantime.

Yes, I agree with all you say. The best solutions are closest to these people’s homes. Ideally, a just and non-persecuting regime or rebel group. Next a processing solution close to home. Finally, better treatment by receiving countries.

But even if receiving countries turn asylum-seekers away, tey could do it with compassion. My real rock-bottom concern is that we as a people have become callous and uncaring, which diminishes us as well as those seeking asylum.

Thanks for your thoughts.